Gender Inequality at Senior Management Levels of Ambulance Staff

Info: 7153 words (29 pages) Dissertation

Published: 16th Dec 2019

Tagged: ManagementEquality

Chapter 1: Introduction

- Research Justification and Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to investigate a whether female staff employed within the Ambulance services of England perceive gender inequality at senior management levels are due to barriers previously identified in research undertaken in other industries.

There is a vast swathe of literature which evidences the existence of gender inequality across many industries and cultures. It recognises various causes; however no research has previously focused on the Ambulance Service. The research will identify initially if there are gender inequalities, then identify the perceived barriers.

1.2 Background

Across England Clinical Commissioning Groups commission 10 regionally based ambulance trusts to provide urgent and emergency healthcare, (there are separate arrangements for the Isle of Wight). Many Ambulance Trusts also have contracts to provide a range of other services, e.g. patient transport (PTS) and NHS 111. In 2015-16, these combined services cost about £2.2 billion, of which £1.78 billion commissioned urgent and emergency services. In 2015-16, the ambulance service received 10.74 million urgent or emergency calls which led to 6.6 million face-to-face attendances (National Audit Office 2017).

Ambulance services assess and treat many people with serious or life-threatening conditions, however they also provide a range of other less urgent and planned healthcare and transport services.

Ambulance crews can include a range of medical staff, such as paramedics and EMTs (Emergency Medical Technicians – not as highly trained as paramedics but still able to assess and treat some conditions). Paramedics are highly trained in all aspects of emergency care, from trauma injuries to cardiac arrests. Some patients will always be taken to hospital when there is a clinical need for this; however, paramedics now carry out more diagnostic tests and do basic procedures at the scene. Many crews also refer patients to other health services e.g. GPs, Social Care, Community Nurses, and directly admit patients to specialist units such as major trauma centres or stroke units.

As previously stated, non-emergency transport services are commissioned by Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and it remains up to local CCGs to decide how these services are delivered and by whom. Unlike the Paramedic Emergency Service, where there are a limited number of NHS Trusts with the capability to deliver the service, PTS is transport only and can be provided by private providers like Arriva and Trust Medical.

For the purposes of this research, the author will focus only on the Paramedic Emergency Service element of the Ambulance Services. The reason for this is, the other facets are additional services added through time to the core function of Ambulance Services, and the services themselves perceive the Paramedic Service as their core function.

Ambulance services across the UK started after the Second World War in 1946 with the National Health Services (NHS) Act which came into power on 5th July 1948. The NHS Act of 1946 was replaced with the National Health Services Act 1977.

At its commencement, the ambulance service was staffed through volunteers, and training consisted of basic first aid training akin to that given to the Civil Defence Corps, however in 1964 a report composed by a number of working parties (the Millar report) recommended patients should receive treatment and transport.

This led to the establishment of ambulance training schools where “ambulance men” received training in basic first aid, and some extended skills in the use of oxygen and Entonox.

From 1974 each ambulance service was transferred to the NHS at a local area level and as a result differences in training and equipment soon started to arise, a trend which still happens today. Many ambulance services had previously been run by the county councils and not as the cornerstone of the NHS they are recognised as today.

The last 30 years has also seen the emergence of private ambulance providers, who currently do not provide front-line blue light response but have the capability to deliver some urgent and routine transport.

Organisations such as Arriva and Care UK, have established themselves as non-emergency ambulance transport providers winning contracts throughout England to transport patients to out-patient clinic appointments.

Reflecting on the history of the establishment of both public and private sector ambulance services it is apparent these organisations arise from significantly different origins and therefore their staff profiles have evolved through significantly different pathways.

Public sector arose from volunteers from the Civil Defence Corps, male centric, male led and then through being run by county councils – men in suits. To today when we see a workforce with an equal split of male and female professional clinicians yet still male dominated operational management teams.

Despite the introduction of employment legislation over the past 46 years (e.g., Equal Pay Act 1970; Sex Discrimination Act, 1975; The Equality Act 2010), and the recognition of a mandatory requirement for diversity training, there still remains significant inequalities between men and women in the workplace.

Currently across the English Ambulance services there are approximately 17,900 personnel working in paramedic services across the English ambulance trusts. Of those 1% are managers in Band 8 or above (NAO 20170. Information gained from a number of ambulance services via a Freedom of Information request, it was revealed the number of females in these managerial roles is just 26. Many of these roles are categorised as “managers” however do not have managerial responsibility or decision making, for example in South West Ambulance Service trust (SWAST) they list one of the managerial roles as Pharmaceutical advisor.

This project aims to investigate whether there are barriers to women achieving gender equality in senior operational management roles in the ambulance services of the UK. Over the last 10 years the percentages of men to women working in the ambulance service has significantly changed, in the 2015 Annual Report of North West Ambulance (NWAS) the male: female gender splits were reported as 17% women in Executive and Non-Executive positions (male 83%), in senior management roles 30% women (70% men) and overall organisationally for all employees 45% female (55% male).

Is there any evidence that there is gender discrimination within the ambulance services that is inhibiting the career progression of women? In 2015 the King’s Fund produced a short report investigating discrimination perception of employees of many organisational types across the NHS. Table 1 presents a summary table taken from that document which identifies there is more discrimination across most areas within the ambulance service (highlighted in yellow), but gender discrimination (highlighted in red) compared significantly higher to all other NHS organisations.

Human Resource Management (HRM) is the central lens that will be used to analyse current discussions. Recruitment and HRM Policy development are relatively well researched and reported, and will be used to investigate impact on the ambulance services across England. This study is worthy in exploring the intended and unintended consequences of HRM, as these can impact on careers of male and female employees and has not previously been applied to the ambulance service sector.

The literature review within the dissertation will include a review of theories including tokenism, quotas, gender and leadership style, recruitment bias, and stereotypes which contribute to building an understanding of impact on career progression. It will also investigate the impact of tokenism on employee retention, decision making and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

The assimilation of equality and diversity of diversity does not develop naturally. Organisations must take specific steps to make it happen. This means there must be extended ownership and establishing “buying in” from all managers through the self-setting of objectives and improvement plans. To support, organisations must introduce goals that identify specific equality and diversity measures that will empower managers to manage (Rutherford and Ollerearnshaw 2002).

Accountability is the key to driving the change. Giving managers ownership then holding them accountable for equality and diversity aligned to all other business objectives they have ensures the organisation demonstrates it views equality and diversity equitably to its other business priorities. Where this has already been adopted, the organisations view equality and diversity as having a significant positive impact on their business (Rutherford and Ollerearnshaw 2002).

Many research articles demonstrate that improved performance within organisations is an outcome when the diversity of the management team mirrors that of the workforce (Gonzalez 2012) or has an impact on Corporate Social Responsibility (Larrieta-Rubin de Celis et al. 2015).

- Aim

To investigate whether there are barriers to achieving gender equality in senior operational management roles in the English Ambulance Services.

- Objectives

- Identify if gender inequality does exist in the Ambulances services across England;

- Evaluate whether employees perceive HRM (Human Resource Management) inhibits females’ career progression;

- Evaluate whether ambulance staff notice the presence of unconscious bias and tokenism as contributory factors.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.0 Introduction

The following chapter will introduce and critically review the literature themes identified within

research aims and objectives with a view to gain an insight into previously published empirical research.

2.1 Gender Inequality

Gender inequality fluctuates at different phases in careers, but is most noteworthy at senior levels in organisations; whereas graduate entry roles equate to a relatively equal representation of men and women, this equality is preserved up until junior management level. As staff members advance into middle management, senior management and leadership positions, numbers of females significantly decrease, it being four and a half times more likely that men achieve positions on executive committees compared to women entering the workforce at the same time (Cracking the Code, 2014).

This qualitative document presents some provocative talking points however within the paper the assumptions are not referenced by legitimate and recognised research. The data presented however does reflect the current climate within the Ambulance services across the UK. Across the UK levels of reported discrimination vary considerably by type of trust, gender, age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion and disability status. Ambulance Trusts have the highest levels of reported discrimination and of the discrimination types reported, gender discrimination features highest (King’s Fund 2015).

With the exception of the King’s Fund paper and some NHS documentation very little research has centred on the Ambulance service. The author therefore will be utilising research published within other fields of business to identify theories and then will test these in this research dissertation in the ambulance service setting.

The expanding volumes of literature examining women in the United Kingdom proposes that women do have a different effect on business and society than men; this is clearly

illustrated in gender differences in political priorities and standpoints among British politicians Lovenduski and Norris, (2003); Childs, (2004). It is recognised that modern and innovative analysis approaches are needed to reveal a better understanding of the gender dynamics of institutions and institutional change (Kenny 2007).

Feminist researchers seeking to theorise about organisations find it difficult, as there are deeply entrenched sexual categorisation within organisational theory and practices. Some of the practices are conceived to exclude females. This core interpretation is more than just a mistake, as it forms some of the organisational foundations of businesses. The omission of women creates a concept of exclusivity which can only be overcome through changes and disbanding of the practices and restoration of females in senior positions (Acker 1990).

The purpose of feminist theory is not only to highlight the stagnation of gender interactions but also to propose change through research. Feminism is a complex and multi-faceted research discipline which I can merely refer to within the dissertation. The literature review will consider concepts much wider than only that of the feminist.

“Sameness feminism” predominantly appeals to tolerant feminist theories from two schools of thought; ‘liberal individualism’ and ‘liberal structuralism’. The two theories aim to reduce the variances between the genders perceived in life today, to enable women to ‘compete’ on a level playing field with men. From this perspective, gender differences are created by societal socialisation, not through natural occurrence. Liberal individualists however challenge further, that this societal socialisation leads to deskilling of women and leads to an inability to operate in a male-dominated organisation (Nentwich 2006).

Liberal individualists emphasis equipping women (Ely and Meyerson, 2000), liberal structuralists emphasise the structural barriers preventing or hampering females progress within male-dominated businesses (Kanter 1977).

Power structures with distinct gender differentiation provide fewer means and opportunities. To generate the environment that supports females to achieve equality, the organisational barriers must be reduced. Whilst the cultures aligned to masculine-dominance become the norm and are unchallenged, women have to adapt. Within these environments change should be centred on changes in legislation, changes to policies and procedures, which could include coaching and mentoring, career pathway redesign, flexible working contracts and any other initiatives that would facilitate breaking down the discriminatory barriers to enable women to achieve equality. This, however, all leads to the dilemma of equality meaning same, and there is a huge danger if we strive for sameness when in reality men and women are different (Nentwich 2006).

The key objective of difference feminism, is to even out the hierarchical variations between women and men. To achieve this, it is vital that the variations are both acknowledged and appreciated. Women are different to men and live in society within their space and function. When growing up they have different life experiences and are exposed to numerous male and female figures. Difference feminist approach would strive to install diversity training and other education to highlight gender differences and to re-evaluate them. This may include rating the manner in which a female carries out a task, with a view to their skills that would not be demonstrated in a man, however there is a significant danger in doing this as it may reinforce gender stereo-types and highlight the differences further (Nentwich 2006).

Ely and Meyerson in 2000, compared sameness feminism and difference feminism and concluded that it was impossible to define the problem within each of the theories as sameness and difference were inextricable linked. Whilst there are hierarchical variations both feminist theories agree and that these need to be tackled to overcome inequality both sameness and difference feminism disagree in regard to how this change should be approached. Therefore, both viewpoints must be considered exclusive. Difference feminism accept as true there are irreversible differences between males and females, sameness feminism believe men and women are the same. Difference feminism would question the hierarchical link of women and men, sameness feminism sets out to eliminate these differences. These conclusions are opposing, and if it is assumed only one theory can be true at a point in time, it leads to feminist researchers having to choose their approach. These dilemmas of sameness and difference feminism have been discussed for many years, and post-equity methodologies have been suggested as a conceivable way forward (Lorber, 2000; Scott, 2006).

Krook (2010) identified a framework which brings together both feminist and institutional theories producing new perspectives in relation to gender and politics and the influence of organisations. If the framework is utilised institutionalism scholars could gain insight into how gender influences a range of political portents, while feminists could broaden their concept through the use of the new framework to attain improved structured research to push forward the feminist theories in mainstream political science. Using the same argument, institutional theorists will gain from feminist insights especially if they consider initiating the subject of gender into their research analysis especially around topics like power within institutions.

Krook (2010) concluded that combined approach of feminism and institutionalism may be overly intricate in relation to candidate selection, however the framework could be used in many other political studies.

2.2 Is Human Resource Management (HRM) inhibiting females’ career progression?

Norway became the first country, in 2003, to introduce legislation that all boards of

public companies must have a 40% female representation. In 2014 women make up 40.7% of non-executive director (NED) positions. This is progress however, only 3% are CEO’s and only 6.4% are females in top management positions. So, with quotas change does occur at the top layer this does not appear to be replicated at lower levels of the hierarchy. Beneath board level, women remain under represented within senior management positions (Bertrand et al. 2014).

Acker (1990) introduced a systematic theory of gender to breakdown gender segregation and identity, to create more democratic and supportive organisations. The theory was by reducing hierarchical male-dominated organisational behaviour, women would be less oppressed.

The Davies Review (2015), reported the progress, against defined stretch targets, made over the previous 5 years of reform aimed at exploratory gender equality on company boards in the UK, and was the catalyst for change in this area. The initial report highlighted the inequality between men and women at senior levels. Today the report cites 25% female representation on the FTSE 100 as a major milestone in the journey to achieve gender equality.

Are quotas and stretch targets the answer; perhaps not? Sojo et al. (2016), found in their research that quotas without legislative enforcement were ineffective and Dubbelt et al. (2016) went further to suggest that despite quotum being an effective strategy to increase the number of female managers in an organisation, this may not eliminate other barriers women experience when striving for career progression.

Apparent career outcomes highlight inequalities between men and women in the

workplace. Research shows multiple areas of management in which women are

disadvantaged (Romei & Ruggieri 2013, Posholi 2013, Shih, Young & Bucher 2013).

There are obvious inequalities in the career progression paces of men and women. Research suggests that these disparities originate from variances in the way men and women are judged for promotion, having to prove their competence more than men. (Beeson & Valerio, 2012, Biernat & Fuegen, 2002). Silva, Carter, & Beninger, (2012) also found that following the attendance on a development program in leadership men were promoted in preference to women.

Silva et al. (2012) studied a cohort of MBA graduates comparing the males to females; the findings were that the males’ project allocations had double the budgets, were more prestigious, offered greater exposure and led to superior attractive roles than that of the females.

Modelling carried out by Perry et al. (1994) suggested that recruitment can often be based on gender and suggest HRM have the ability to enforce organisational policy changes and training programmes to eliminate biased recruitment. Luzadis et al. (2008) reached further into the theory of bias and recruitment by examining the potential impact of “prescriptive gender bias” on the criteria for selection during recruitment. Although this study has some limitations, in that it used students as decision-makers without experience, this study does provide an excellent framework to utilise in this research as part of the gathering of female middle managers’ perspectives on career progression and recruitment. This dissertation will consider these theories and limitations and through a questionnaire of women employed in the Ambulance Service seek responses to the hypothesis of recruitment bias.

It has only been fairly recently that businesses and policy makers have recognised gender bias as a factor of workplace inequality. The sex discrimination case of Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins (1989) created the cornerstone that underpins gender inequalities in the workplace. This is now referred to as gender bias; such attitudes or beliefs about men and women, their different aptitudes, skills and standing in society. Social psychologists suggest gender attitudes are a significant contributor to gender inequality in the workplace (Wessel et al. 2015).

Bias can present on a conscious or unconscious level. Conscious bias is intentionally formed and can be consciously displayed (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). In contrast, unconscious bias is associated with a triggered reaction to a situation, personal trait, or object an individual comes into contact with (Rudman & Ashmore, 2007). Individuals may not be aware that they hold such associations.

Jackson et al. in 1991 supported the proposition that HRM policies and practices are in part responsible for the workforce demographics in situ in organisations. This is an important consideration in the context of gender inequality in senior management roles, and will be considered in the research presented. As this finding was more than two decades ago more recent literature has been reviewed and Mannix and Neale (2005) tender the argument that the businesses and the leaders within them must lead the change through many forums. They refer to mentoring, training, and learning across the whole workforce. Giving minority groups, in the case of this research female mangers in the Ambulance Service, legitimacy not only provides opportunities but also inspires more junior staff members to be ambitious as they see better prospects.

Is it therefore only organisational policies, developed and implemented by the organisational leadership that will facilitate change? Gibson found that as women have fewer role models in senior and executive roles they are met with the onerous challenge of translating behaviours displayed in male role models into behaviours that have some meaning to them (Gibson 2004).

Many research articles recommend different policy solutions to the complex multi-faceted dilemma of gender homogeneity. Back in 2002 Martins et al. analysed data from just under 1000 managers to identify if there was a conflict between work and family linked to career satisfaction. They found the least conflict in managers working in organisations with supportive HRM policies and greatest conflict in male dominated organisations. More recently Crowley and Kolenikov (2014) examined if flexible working options did harm career progression. They found there was no statistically significant impact on stunting career progression, however they also revealed that flexible working policies were not as supportive to female staff as flexibility of time off.

This research through the questionnaire will identify what policies are in place across the Ambulance Services of the UK and investigate if it is perceived that these policies have been advantageous or detrimental to the career progression of female middle managers.

2.3 Is stereo-typing curtailing opportunities for women?

Conscious bias is based on beliefs and stereotypes. As described in social role theory (Eagly & Maldinic, 1989 and 1994) attitudes related to traditional role types between men and women are at the origin of discrimination. These mindsets stem from learnt standing differences between the genders; men are more likely to become leaders; men traditionally are the breadwinners in the family while the women are homemakers (Biron et al. 2016). Discrimination in the workplace occurs when women are perceived to step outside of these preconceived “norms”. Heilman & Okimoto (2008) found working mothers were considered less competent than both men and non-working mothers. Further research more recently by Heilman & Okimoto (2012) unveiled that mothers who chose to go out to work were perceived poorer parents than non-working mothers and fathers who worked.

Stereotypes are beliefs related to different skills, traits and abilities men and women

exhibit. Previous research proposes that grouping of “type” can be described by different components (Judd, James-Hawkins, Yzerbyt, & Kashima, 2005). Some researchers refer to these as “warmth” and “competence” (Cuddy, Glick, & Beninger, 2011; Judd et al.., 2005). Others use “agency” and “communality” as the two key components (Eagly & Johannesen, 2001; Williams et al. 2010). Originating from the traditional women-type roles, warm and communal traits are perceived as associated with women (i.e., caring, helpful and sensitive), on the other hand men are linked with competence and productivity needed to succeed in the workplace (i.e., assertive, dominant and decisive). Discrimination occurs when women are considered non-traditional female roles, for example, management and leadership positions which are stereotypically masculine (Dennis & Kunkel, 2004; Powell, Butterfield, & Parent, 2002; Scott & Brown, 2006). This discrimination can lead to low or negative expectations of delivery i.e. women will not be competent and therefore not deliver the performance a man would. This bias leads to women being overlooked for promotion and development opportunities (Hareli et al.., 2008; Heilman, 2001; Bosa & Sczesny, 2011; Latu et al.., 2015; Landy, 2008).

2.4 Does the presence of tokenism contribute to the discrimination?

Tokenism exists when only a few representatives of an under-represented group occupy power-roles in an organisation (Anisman‐Razin & Saguy 2016). The expression of considering a minority representative as a “token” was first created by Kanter in 1977. Past research has demonstrated conflicting views on the impact tokenism on female career progression with Zimmerman (1988) suggesting it has limited value while Gardiner & Tiggemann (1999) consider tokenism to contribute to increased stress levels in women in tokenistic situations.

Schwab et al. (2015) analysed the impact of managerial gender diversity on performance within organisations and found both positive and negative consequences. They allude to negative outcomes discouraging some businesses, however from a positive perspective evidence the further firms move from tokenism into parity the greater the performance benefits that are yielded. The research is however limited to organisations in Portugal and due to confidentiality, they were unable to explore in more depth any external factors impacting on the business performance.

Knowledge of the impact of tokenism and the associated skewed gender ratios within organisations reduce the likelihood of women aspiring to senior roles within that setting (McDonald et al. 2004). Pettigrew (1979) goes even further saying tokenist individuals will be isolated by dominant groups when their delivery results in a negative outcome, and if the result is a positive one, no credit is apportioned to the token, instead it will be perceived as luck or manipulation of the facts or a one off. Pettigrew’s research however took place sometime ago and a reduction in gender discrimination has progressed greatly in that time, however as demonstrated in the King’s Fund paper, the Ambulance Service seems a little behind the curve when compared to other NHS institutions.

So, what is the critical mass that brings about homogenous gender representation? Torchia et al. in 2011 examined whether an increase in the number of women on corporate boards created critical mass that would have a significant impact on the innovation of the business. The paper uniquely examined the contribution of women on the board rather than their influence. It concludes that there is much more research to be done, however does allude to 3 females on a board being the minimum to overcome stereo-typing and marginalisation by the men. What impact does this have on women attempting to progress to senior management roles within the Ambulance Service? There is a well identified gap in the research published to date, which this dissertation will examine through a questionnaire sent to Ambulance service middle managers.

The impact on organisations goes beyond its staff and its performance, the impact on its reputation and stakeholders’ views through its Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) can damage the business. Bear et al. (2010) found having more females on boards of large health care firms did improve the CSR ratings, however the study also found that there was no detrimental effect by not having the diversity. More recently this argument has been countered however by Larrieta-Rubin de Celis et al. (2015), with research investigating the impact women in management roles have on CSR. The research examined women at various management levels in organisations influencing gender equality though CSR practices. This paper reaches into the previously unexamined middle management sphere and analyses the tangible effects on a business’s CSR outcomes and concludes support for that hypothesis. This research has some limitations in that the companies sampled were in Spain and the sample survey was small, however this provides an opportunity for further research in the UK in relation to female middle managers and their potential impact of organisations’ CSR.

Chapter 3: Methodology

3.0 Introduction to Research Methods

As outlined in the literature across non-ambulance industries there are numerous barriers that exists which contribute to gender equality. This research will investigate if some of these barriers exist preventing gender equality in senior operational management roles in the Ambulance Services across England.

The research will gather ambulance staff’s perception of the existence of any barriers, and from the findings of my literature review into barriers found in other industries, identify if this is reflected in practice within the ambulance sector. People’s views, interpretations, experiences, interactions are integral to understanding this reality.

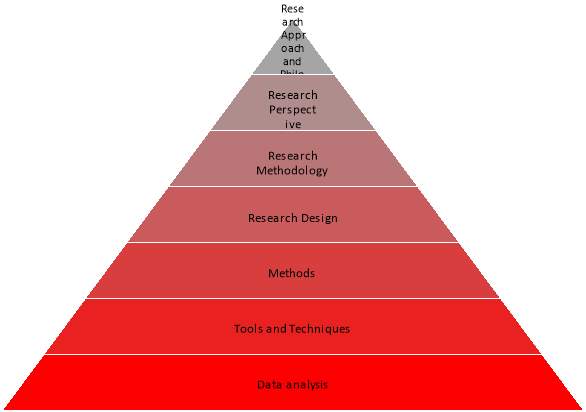

This chapter describes the methodological approach used to address the main research aim

and objectives. Figure 1 below, illustrates the” Research Hierarchy” described by

Maylor & Blackmon (2005) on the principle that the researcher’s primary approach and

philosophy towards a study influence both the methodology and research design.

Identification of a research philosophy will be set out along with the justification of the chosen data collection method and method of data analysis in this empirically based dissertation. Within the limitations of the research aim, only non-ambulance sectors have been investigated, therefore to provide any significant contribution to gender equality research, primary data must be gathered.

Prior to the research philosophy being outlined and the research methods explained, the main aim and objectives of the research will be restated. A clearer description of the objectives is outlined as a result of the review of the existing research literature.

Fig. 1 “Research Hierarchy” [adapted from Maylor and Blackmon (2005)]

The empirical study aims to identify if ambulance staff perceive there are barriers preventing gender equality in senior operational management roles.

The research objectives are:

- Through the research identify if there is equality of representation of both men and women in senior management roles within the English Ambulance Service Trusts

- Evaluate whether HRM (Human Resource Management) inhibits females’ career progression;

- Evaluate whether the presence of unconscious bias during recruitment prevents women achieving senior management roles;

- Identify if tokenism is perceived as a barrier within the ambulance service and hence has a contribution to gender inequality.

- Ascertain if females in the ambulance service have female role models?

- Evaluate if females are inhibited from applying for promoted post due to HMR policies?

3.1 Research Approach & Philosophy

In order for knowledge to continue to be uncovered, and understanding or improvements in practice presented then research must be carried out (Hwee Ang, 2014).The research approach adopted within the study is governed by the philosophy of the research paradigm.

Traditionally research approaches have been framed by the basic choice between positivistic and modern research frameworks or more interpretive and postmodern

frameworks (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006).

Positivism and Interpretivism are two opposing paradigms. It is essential to ascertain which of the two is more relevant to this study as the selected framework will dictate by what method the scientific research will be conducted. (Saunders et al. 2016).

The positivism paradigm, in the context of social science experiences, supposes that such events can be evaluated through the study of links between variables and seeks to uncover a system of cause and effect inter-relationships. The nature of reality, or ontological hypothesis of positivism accepts as true, facts and data free from human influence. The epistemological assumption would concentrate on uncovering measurable and observable data and realities, and only evidence that can be seen and measured would be credible (Saunders et al. 2016).

Interpretivism on the other hand believes that social phenomena are subjective and created by human perceptions. The ontological assumption is that multiple realities exist. As reality is subjective, and the behaviour of natural objects contrasts significantly from that of human behaviours, social reality is subjective (Maylor & Blackmon, 2005).

Epistemology, or what each of us counts as knowledge, is a relationship between, in this case, the researcher and their own background, experiences, culture and beliefs. (Punch, 1998)

Positivism and interpretivism are polar opposites on a line of various paradigms which can exist in concert. On that line, a little less extreme than positivism and interpretivism is a common paradigm associated with both feminist and business and management research – Social Constructivism. As described in the interpretivist methodology, social constructivism focusses on examining the how individuals interpret the world around them, however it proposes that reality is formed through social interaction in which people construct, to some extent, shared realities and values. The research does not seek to label or limit complex perspectives but aims to decipher a group’s interpretation by asking questions to make sense of individuals perspectives (Saunders et al. 2016).

As the aim of this research is to comprehend social phenomena the social constructivism paradigm supports the understanding of people’s perspectives. This will lead to greater clarity in discovery of the social phenomena being researched.

3.2 Research Perspective

Feminist research is most often aligned to qualitative research rather than quantitative. Mies (1983) identified that quantitative research often disregards the voices of women, studies them in a non-recognised manner and turns them into objects.

Qualitative research is not centred on a unique organisational and hypothetical concept but is directed towards meanings and relationships between the meanings (Flick, 2009).

Quantitative methods concentrate on testing and verification of a concept. Within this piece of research, the concepts of gender inequality have been discussed previously in numerous research pieces, however there is no published research that explores this concept in Ambulance Services.

This research is designed to gain insight into staff perspective on gender inequality and any potential causes, the need to establish some quantum is required to provide context (Quantitative research) however qualitative research methodologies will be applied to provide the research with an interpretation of the relationships between the quantitative data sets, therefore a mixed methods approach will be adopted.

The key areas to be explored in this research are in relation to barriers leading to deficiency of female senior managers in the operational aspect of the ambulance service; these include tokenism and gender bias, unconscious bias, HR policies and process during recruitment, and role models and leadership qualities.

From the literature review it appears these are the key themes within business that create gender inequality, but that can be changed with the right organisation leadership and drive.

3.3 Research Methodology & Design

As outlines in the previous section, the theory of gender inequality has been researched for many years and the concept is well recognised. The researcher however describes that the theory has not been applied in the Ambulance service sector: for this reason, the researcher proposes to adopt a deductive research design to this study.

Deductive research produces empirical evidence to examine theories (Saunders et al. 2016). It involves rigorous testing through a number of proposals, for example within this research piece gender inequality has been proven, however does it exist within the ambulance services across England, what elements exist (tokenism, unconscious bias, stereo-typing), do staff employed perceive them to be present and what do they suggest can be done to control these phenomena?.

As this research study aims to test previously identified concepts it will take the form of a questionnaire containing a mix of open and closed questions. The advantages and disadvantages of using questionnaires as a method of collecting the data was considered. Table 2 below outlines the options and the limitations of various methodologies:

There are further advantages to the use of a questionnaire which include, anonymity provides respondents to express their beliefs, which is important when considering gender inequality (May 2010).

The questions will be a mix of open and closed questions; however, the dominance will be closed questions to enable the researcher to carry out thematic analysis of the responses.

Some classification questions are at the start of the questionnaire to enable the study to ensure it identifies the correct cohort of respondents thus taking steps to eliminate contamination. The questions will be constructed within the context of the themes identified in the literature review of identified gender inequality phenomena.

Prior to distribution of the questionnaire the researcher considered all methods of circulation. A summary of the options considered can be found in Table 2 in Appendix 1.

From the options available, it was concluded that one option in isolation would not meet the needs of the author to get the questionnaires geographically spread across the whole of the north west, and target female staff working or having previously worked in paramedic operations.

The author has a significant contact list, so decided to email the questionnaire to all on that list. The author is also an active member of a NWAS internal restricted social media group of women leaders, so the questionnaire was posted on this site.

As the researcher attends many departments and meetings during the working week, printed copies of the questionnaire were taken to numerous settings and appropriate personnel were asked to fill the questionnaires in.

Consideration was given to use an electronic survey tool, however the organisation she works for only uses survey monkey, and this tool is not supported for use by the university for research.

By the 3 methods (email, web and hand-delivered) 86 questionnaires were returned by several methods (email, post and by hand) to the dissertation author.

This represents XX% of the estimated target population.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Equality"

Equality regards individuals having equal rights and status including access to the same goods and services giving them the same opportunities in life regardless of their heritage or beliefs.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: