How Do Investors React to CSR Announcements?

Info: 14931 words (60 pages) Dissertation

Published: 13th Dec 2019

Tagged: CSR

Literature Review on

How do investors react to CSR announcements? Evidence from India, an emerging economy

1. Introduction

1.1 Defining Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) or the responsibilities of businesses towards the society, as a concept, has been gaining increasing attention both from the academia and the industry practitioners ( (Grayson & Hodges, 2004); (Benn & Bolton, 2011); (Pearce & Manz, 2011)). Marrewijk (2003) claimed that CSR and corporate sustainability (CS) conveyed the same meaning and defined both the terms as corporate sustainability and, CSR that refer to the set of a company’s voluntary activities, which demonstrate the inclusion of social and environmental concerns in its operations and in interactions with its stakeholders.

Hopkins (2007) asserted that defining CSR was undoubtedly essential and opined that CSR is concerned with treating the stakeholders of the firm ethically or in a responsible manner, which meant treating stakeholders in a manner deemed acceptable in civilized societies. Social includes both economic and environmental responsibilities and since stakeholders exist both within a firm and outside, the wider aim of social responsibility is to create higher standards of living, while preserving the profitability of the corporation, for people both within and outside the corporation. This definition, however, was plagued by problems in defining universally acceptable benchmarks of “civilised societies”, representing nature as a valid stakeholder and constitution of “higher and higher standard of living” (Russell, 2010).

Blowfield & Murray (2008) contend that instead of looking for universal definitions of CSR, companies need to formulate their strategies to benefit the stakeholders. Since the definition by Marrewijk (2003), together with the one by Hopkins (2007), encompasses all the five dimensions of CSR (viz., stakeholder, social, economic, voluntariness and environmental) proposed by Dahlsrud (2008) where 37 definitions of CSR were analysed, these definitions may be adopted to provide a rudimentary knowledge of CSR.

1.2 CSR in India

CSR in India has been conventionally considered as a philanthropic activity and was performed with little or no deliberation. Consequently, there is inadequate documentation on CSR activities in spite of the fact that it always had a national spirit embedded deep within it. The CSR activities ranged from endowing different institutions to actively participating in India’s freedom struggle and promoted the Gandhian concept of trusteeship.

In the 1990s, CSR gained traction in India, with many corporate houses adopting philanthropic practices. The Tata Memorial Centre, one of the best cancer hospitals in Asia, treats over 70% of their patients almost free of any charge. The Infosys Foundation, set up by the Indian IT giant, Infosys, was established in 1996 to support the underprivileged sections of the society. “The Infosys Foundation supports programs in the areas of education, rural development, healthcare, arts and culture, and destitute care. Its mission is to work in remote regions of several states in India. The Infosys Foundation takes pride in working with all sections of society, selecting projects with infinite care, and working in areas that traditionally overlooked by society at large. At the outset, the Infosys Foundation implemented programs in Karnataka, and subsequently extended its coverage to Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Bihar, Delhi, Gujarat, Jammu & Kashmir, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Orissa, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand and West Bengal.” (Infosys Foundation, 2016). The Azim Premji Foundation, established by the Indian IT giant WIPRO, “works in 8 states which together have more than 3,50,000 schools” (Azim Premji Foundation, 2016). However, the Government of India became disgruntled with the progress of spending on CSR activities by Indian businesses and after a 4-year period of vacillation between whether to make CSR spending voluntary or mandatory, finally made CSR expenditure mandatory through the Companies Act, 2013.

2. Literature Review

2.1 CSR Models

2.1.1 Ackerman’s Model

In 1976, Ackerman (Ackerman & Bauer, 1976) proposed a CSR model, which could be implemented in three phases, viz., recognition of a societal problem, studying the problem intensely and find out solutions by hiring experts and finally, implement the proposed solutions. However, other parameters and restrictions of CSR activities were outside the purview of this model.

Source: Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business horizons, 34(4), 39-48. Page no. 42

2.1.2 The Pyramid Model of CSR

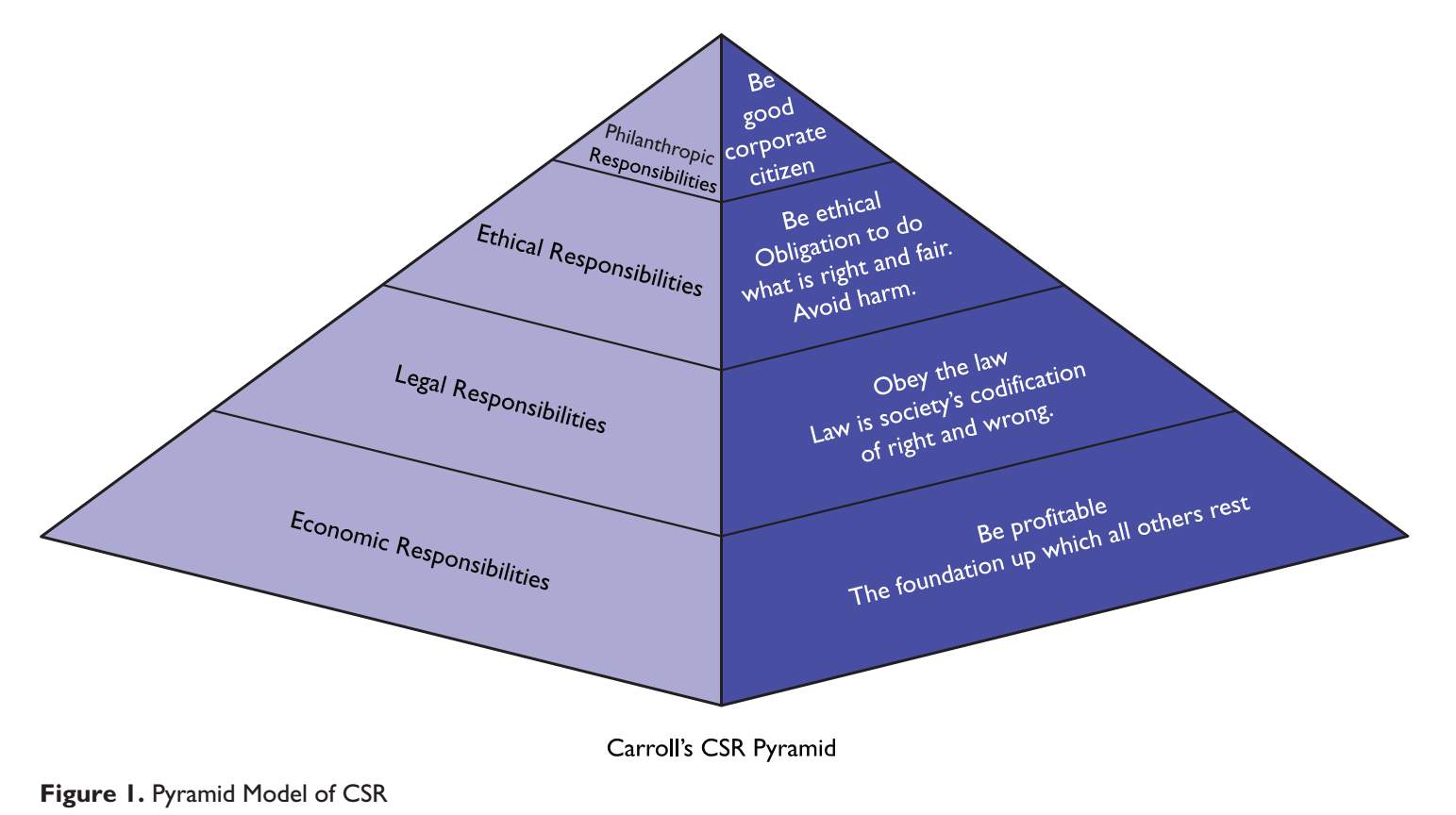

Carroll (Carroll, 1991) proposed the pyramid model of CSR (Figure 1), which comprised of economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic responsibilities, in decreasing order of priorities. Carroll further stated that all other responsibilities depend on the economic responsibilities of the firm, failing which, all its other responsibilities would become doubtful considerations.

Source: Schwartz, M. S., & Carroll, A. B. (2003). Corporate social responsibility: A three-domain approach. Business ethics quarterly, 13(04), 503-530. Page no. 509

2.1.3 The Intersecting Circles Model of CSR

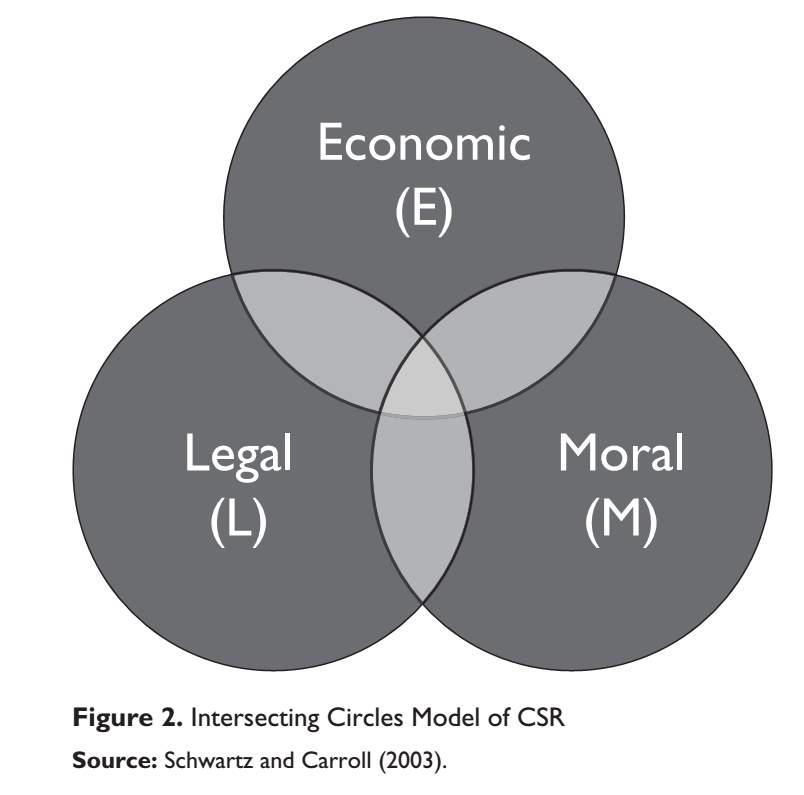

This model (Figure 2), proposed by Schwartz and Carroll (2003) integrates the three aspects: economic, legal and moral and assert that with respect to CSR, none of the aspects is more important than the other.

2.1.4 The Concentric Circles Model of CSR

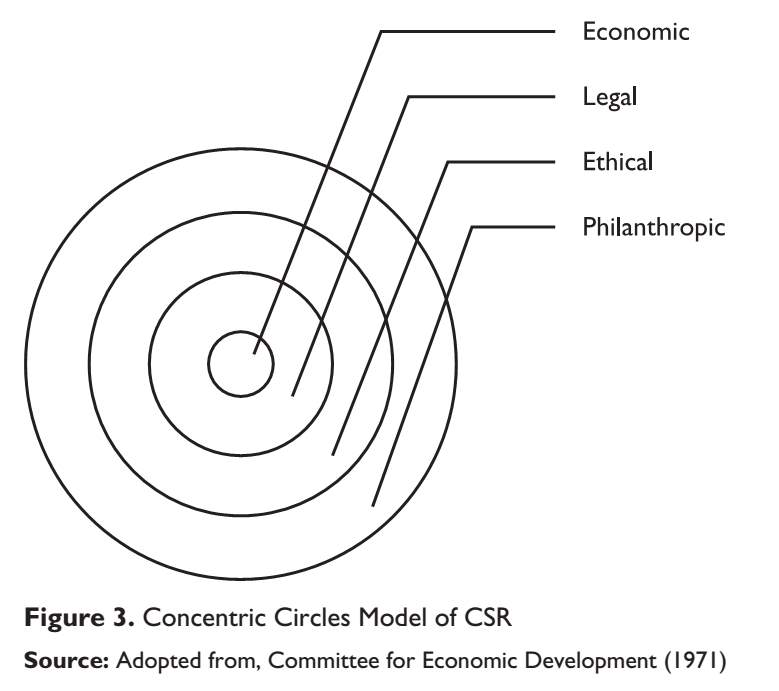

Adopted from a statement by the Committee for Economic Development (1971), this model postulated that social contracts of business processes are not only achievable, but also morally essential and hence advised companies to embrace a more humane approach towards society. Even though the original model has only three rings, viz., (a) economic (products, job, financial stability and growth); (b) ethical (responsibilities to exercise the economic functions with a sensitive awareness of ethical norms) and (c) philanthropic (amorphous responsibilities that businesses should get involved with to improve the social environment), Stone (1975) proposed the legal circle since it encompassed two responsibilities: the first one is to follow law and the second one is to follow the spirit of law.

Figure 4: 3C-SR Model

Source: Meehan, J., Meehan, K., & Richards, A. (2006). Corporate social responsibility: the 3C-SR model. International Journal of Social Economics, 33(5/6), 386-398, page no. 392

2.1.5 3C-SR Model

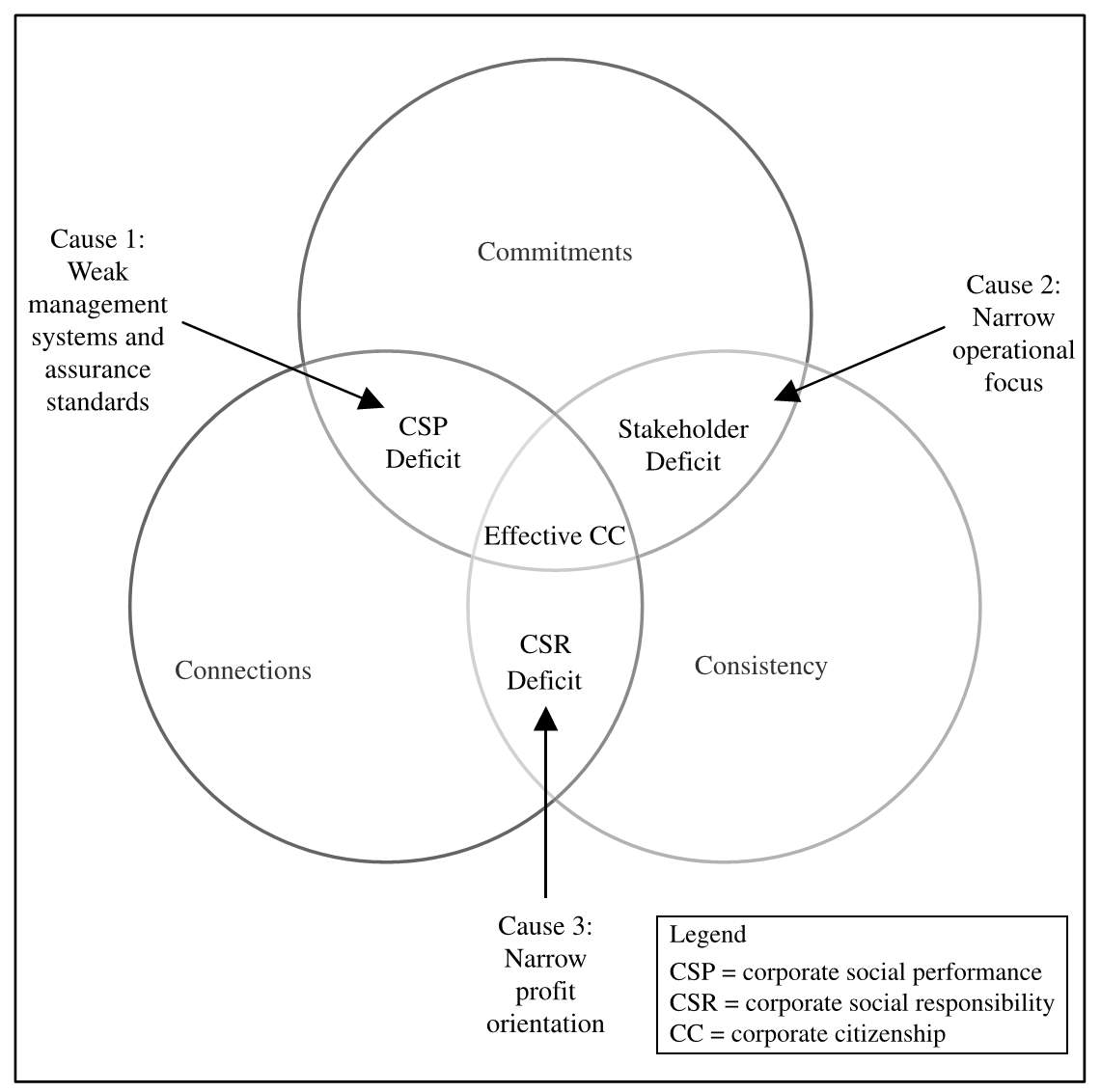

Proposed by John Meehan, Karon Meehan and Adam Richards (2006), commitments (social and ethical), connections (with partners in the value network) and consistency (of behaviour) form the three Cs of the model. The underlying notion of this model was to become good corporate citizens by implementing the three Cs.

2.1.6 Liberal Model

In 1958, American economist Milton Friedman argued that the sole purpose of business was to earn profits. He further contended that firms should operate within the legal framework and create wealth for their shareholders and the social aims could be achieved from taxes and private charitable options (Friedman, The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits, 1971).

2.1.7 Stakeholder Model

This model is attributed to R. Edward Freeman (1984), who posited that the stakeholder model of corporate responsibility was born with the surge of globalization, with which there has been an escalating consensus that with increasing economic rights, the scope of social obligations of industries is also on the rise.

2.2 Indian Models of CSR

2.2.1 Ethical Model

Developed under the aegis of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, this model has its roots in the early 20th century. M. K. Gandhi fostered the ideology of trusteeship, whereby the owners of property would willingly manage wealth on behalf of the people and pressure on the Indian industries mounted to support social commitments. The pressure gained particular momentum during India’s struggle for independence and the Indian corporate houses responded by making donations in cash or kind, to set up schools, libraries and hospitals. Many firms, particularly, the family-run businesses, Ambani (Reliance Industries Limited), Tata (Tata and Sons), amongst others, still continue to such philanthropic initiatives (Kanji & Agrawal, 2016).

2.2.2 Statist Model

The 1st International Summit on Corporate Social Responsibility, jointly organized by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) and the Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM), was held in New Delhi on 29th and 30th January, 2008. It was agreed that with the adoption of a socialist and mixed-economy framework, a second model of CSR has emerged in post-independence India, which was characterized by the co-existence of large state-owned public sector units (PSUs) and privately owned firms (KPMG & ASSOCHAM, 2008). The fundamentals of corporate social responsibility, particularly those related to community and worker relationships, were hallowed in labour laws and management principles. Over the years, the statist model has evolved considerably and has currently been widely adopted (Kanji & Agrawal, 2016).

2.3 Comparing CSR Models

Kanji and Agrawal (2016) analysed and compared the eight models of CSR, keeping the selected parameters as factors and developed the following comparison table (Table 1).

| Parameters | Pyramid | Intersecting circles | Concentric circles | 3C-SR | Liberal | Stakeholder | Ethical | Statist |

| Order of importance | Hierarchical; economic responsibilities first | No particular order | Inclusion system; economic responsibilities at the core | Commitment, connections and consistency are equally important | Priority to economic responsibilities, all other being discretionary | Stakeholders’ needs are priorities | Equal weightage to economic responsibilities as well as social commitments | Government-defined |

| Scope of responsibilities | Narrow | Split | Wide | Holistic | Narrow | Split | Wide, but discretionary | Wide |

| Role of philanthropy | Discretionary | Subsumed within other responsibilities | Integral to the design | Social commitments is one of the 3 Cs | Discretionary; almost nil | Only if it benefits the stakeholders | Integral essence | Partially discretionary |

| Social index | Moderate | Low | High | High | Low | Moderate | High | High |

| Environmental index | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | High | High |

| Governance index | Moderate | Low | High | High | Low | High | Low | High |

| Acceptance | Evolved and adopted | Low | Evolved and adopted | High | Evolved and adopted | Wide | Wide | Wide |

| CSR-CFP relationship | Positive | Positive, negative or neutral | Nonlinear | Positive, negative or neutral | Positive | Positive | Undetermined | CSR dependent on CFP and vice-versa |

| Attractiveness | Low | Low | Moderate | High | Low | High | High | High |

Table 1: Comparison of models based on parameters

Source: Kanji, R., & Agrawal, R. (2016). Models of Corporate Social Responsibility: Comparison, Evolution and Convergence. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 2277975216634478, page no. 8.

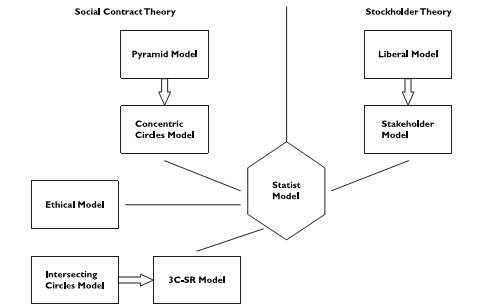

Since the early of its conception, the concept of CSR has been interpreted in different ways. The concept itself has been defined and redefined and several models have been generated. Ignoring the timescale of their development, Kanji and Agrawal (2016) proposed the evolution and integration of CSR models (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Evolution and Integration of CSR Models

Source: Kanji, R., & Agrawal, R. (2016). Models of Corporate Social Responsibility: Comparison, Evolution and Convergence. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 2277975216634478, page no. 14.

The statist model, which India follows currently, has incorporated the best elements of all the models. The first country to legislate CSR, India ranked first in the general category and second overall, according to Asian Sustainability Rating (2010). It is envisaged that with the addition of attributes such as well-defined punitive actions due to noncompliance with CSR regulations, prioritising specific fields for CSR spends and increasing public awareness, the statist model of CSR would improve the performance of Indian businesses both on the financial and sustainable fronts (Kanji & Agrawal, 2016).

2.4 Benefits of CSR

A firm involved with CSR reaps its direct benefits, which serve as incentives for such involvement. While, some of these benefits may be in the form of increased cash inflows or reduced cash outflows for the company, others may be more of a salient in nature. Apart from tax deductions resulting from donations of products, government (local, state and federal) agencies often provide tax credits for CSR and sustainability efforts like using more environment-friendly or “green” materials in production (Sprinkle & Maines, 2010). Sprinkle and Maines (2010) also assert that companies enjoy “free” advertising by doing CSR, since such benevolent activities are generally covered and reported by the public media as news articles.

Several studies investigating the association between CSR and employee engagement have concluded that there exists a strong correlation between employee commitment towards the organization and their perceptions regarding the company’s social responsibility ( (Brammer, Millington, & Rayton, 2007); (Stawiski, Deal, & Gentry, 2010)). As a result, CSR is increasingly being used as a tool to recruit, retain and engage employees (Mirvis, 2012). CSR also motivates the employees by fostering philanthropic firm-contributions from them and ease the implementation of “implicit or trust-based contracts” (Balakrishnan, Sprinkle, & Williamson, 2011).

Firms may also be able to increase efficiencies and reduce costs in the value-chain while engaging in CSR (Sprinkle & Maines, 2010). By adopting sustainable production practices, many companies are aiming at augmenting product reliability and lowering aftersales costs. They observed that apart from using less materials and thereby reducing the allied costs, “green” production contributed towards reducing the cost of quality by reducing both internal and external failure costs. They established that firms expect a positive relation between their CSR initiatives and consumers’ purchasing behaviours. This notion was further strengthened by Nan and Heo (2007) who evidenced that firms involved in CSR enjoy a favourable consumer attitude and increased customer loyalty. Increased customer loyalty translates into higher sales and also an increased tendency to pay and recommend (Harris & Goode, 2004).

2.6 Financial benefits of CSR – CSR & Firm Value

Jensen (2002) proposed a relation between value maximization and stakeholder theory which he called “enlightened value maximization” (EVM). Utilizing considerable structure of the stakeholder theory, EVM accepted that the maximization of the firm value would remain at the heart of any CSR effort. Harjoto and Ho (2015) studied 2,034 US firms from 1993 to 2009 and found empirical evidence that overall CSR reduces analyst dispersion and stock returns volatility ( (Lee & Faff, 2009); (Salama, Anderson, & Toms, 2011); (Oikonomou, Brooks, & Pavelin, 2012)), decreases cost of equity capital ( (Dhaliwal, Li, Tsang, & Yang, 2011); (El Ghoul S. , Guedhami, Kwok, & Mishra, 2011)) and increases firm value ( (Waddock & Graves, 1997); (Blazovich & Smith, 2011); (Jo & Harjoto, 2011); (Jo & Harjoto, 2012)). Gregory et al. (Gregory, Tharyan, & Whittaker, 2014) investigated the effect of CSR on firm value and sought to identify the sources of that value. They analysed 13,089 firm-year observations and concluded that such increased firm value is primarily driven by high CSR performance allied with better long-term growth outlook and lowering of cost of equity capital.

In a more recent study, Mishra (2015) analysed 13,917 US firm-years from 1991 to 2006 to investigate the relationship between post-innovation CSR and firm value. The study found evidence that high-CSR innovative firms are valued significantly higher post-innovation, implying that firms with proven potential growth opportunities, represented by the number of registered patents and their citations, gain by making strategic investments in CSR. Fatemi et al. (2015) combined the effects of CSR expenses on growth, cost of capital and probability of survival and illustrated the influence of interactions amongst these effects on share price. The study’s findings confirmed those of the extant literature and found evidence that the upfront CSR expenses are more than compensated by their positive effects over intermediate and long-term cash flows. The study proved that CSR expenditures increase the probability of survival for the firm and reduces its cost of capital.

2.7 CSR & Cost of Equity Capital

Companies need to see corporate social responsibility (CSR) not only as a means to mitigate risk, but also an opportunity to create value, since they may lower their risk by engaging in CSR activities. In other words, companies, which are not involved with CSR, may experience higher cost of capital, given that company risk is an influencing factor on the determination of the cost of capital (Bassen, Meyer, & Schlange, 2006). The first attempt to explore the relationship between CSR and risk was made by Spicer (1978), who studied the companies that were liable to polluting the environment. He concluded that companies, which maintain better pollution control records, tend to have lower systematic risk, lower total risks, higher profitability and higher price-earnings ratios.

Sharfman and Fernando (2008) and Chava (2010) focussed only on one single aspect of CSR, viz., the environment. Sharfman and Fernando (2008), in their study of 267 companies, found that firms with better environment risk management enjoy a lower cost of capital than others. Chava (2010) applied the implied cost of capital from analysts’ estimates and found that investors demand a higher rate of return on stocks, which are excluded by environmental screens (such as hazardous chemical, substantial emissions and climate change concerns) widely used by socially responsible investors as compared to firms without these environmental concerns. In addition, he also showed that higher rates of interest are charged by the lenders to the companies, which were perceived to be polluting the environment.

In a similar vein, Goss and Roberts (2011) found that banks functioned as “quasi-insiders” of firms and had information which was publicly unavailable. Thus, the banks are in a position to determine whether the investments related to CSR activities benefit the company. This knowledge translates to determine the interest rates offered to companies and the study found that firms with the worst CSR are offered interest rates which were up to 20 basis points higher than the most responsible firms. At the same time, they found that banks do not regard CSR as substantially value enhancing or risk reducing.

McGuire et al. (1988) differed from hitherto literature and evidenced that while performance is more likely to predict CSR than risk, measures of risk also explain a considerable part of the variability in CSR across businesses. Herremans et al. (1993) studied the relationship between CSR measures and risk measures involving large manufacturing companies based in the US from 1982 to 1987 and revealed that firms, which had better CSR reputation, outperform their ill-reputed counterparts by providing higher returns and lower risks to their investors.

There are theoretical arguments towards a relationship between CSR performance and firm risk as well. Godfrey (2005) presented CSR from a risk management standpoint and reasoned that corporate philanthropy may create a “positive moral capital among communities and stakeholders” and the moral capital may facilitate creation of shareholder wealth by providing an “insurance-like protection” to the shareholders. He posited that moral capital provides insurance-like protection for relational wealth because it fulfils the core function of an insurance contract and protects the underlying relational wealth and earning streams against loss of economic value arising from the risks of business operations.

Performing highly on CSR is a crucial determinant in formulating business strategy and analysts and investors perceive CSR as an integral “part of good management” and not as an overhyped trend. Thus, companies with high CSR performance lower their regulatory risk and hence reduce their cost of capital (Bassen, Meyer, & Schlange, 2006). Derwall and Verwijmeren (2007) studied firms over a period of 2001 – 2005 and found that CSR performance reduces the cost of equity capital.

El Ghoul et al. (2011) extended the analysis by investigating the effect of CSR on the cost of capital over a longer sample period. They studied 2809 US firms over a period of 1992 – 2007 and established that high CSR performance leads to a lower cost of equity capital. El Ghoul et al. (2014) further extended the research by studying the effect of corporate environmental responsibility (CER) on the cost of equity capital for manufacturing firms in 30 countries and observed that firms with high CER enjoy a lower cost of equity capital compared to the firms with low CER.

Dhaliwal et al. (2011) found that companies with high cost of equity capital in the previous year incline towards initiating disclosure of CSR activities in the current year in order to reap the benefits of a lower cost of equity capital in the subsequent years. Reverte (2012) studied Spanish firms between 2003 and 2008 and provided evidence that firms with high CSR disclosure practices had lower cost of equity capital. Dhaliwal et al. (2014) extended their research and examined CSR disclosure practices in 31 countries and assert that there exists a negative association between CSR disclosure and the cost of equity capital and this negative relationship is prominent in countries, which are more stakeholder-oriented.

The agency theory developed by Jensen and Meckling (1976) proposes that managers and shareholders maximize their utilities with differing objectives and hence, may have divergent interests regarding the strategic direction of the firm. The neoclassical view, stated by Levitt (1958) and Friedman (1970), deems environmental and social responsibility reduces financial success and held them as means of squandering scarce corporate resources. Jensen (1986) and Stulz (1990) propose that in situations where free cash flow is available and acceptable levels of monitoring mechanisms are non-existent, managers are induced to invest as much as possible, which only benefit them.

On the other hand, suitable monitoring activity levies higher punishment for the unfavourable behavior of managers, and consequently decreases overinvestment. Effective control mechanisms thus provide better internal and external monitoring, reducing the managers’ incentive to overinvest in CSR. Since high CSR performance was associated with enhancing firm value, managers allocate more resources towards CSR. However, at times, managers and large shareholders tend to invest excessive amounts of money in CSR activities since it enhances their reputation as “good global citizens”. Thus, in absence of effective control procedures, investors fear higher expropriation from managers and large shareholders through CSR overinvestment (Barnea & Rubin, 2010). This puts pressure on investors to intensify their own monitoring attempts and hence they demand a higher reimbursement for their efforts (Hail & Leuz, 2006).

Breuer et al. (Breuer, Rosenbach, & Salzmann, 2016) attempted to reconcile the contrary viewpoints of stakeholder and agency theories regarding the effect of CSR on the cost of equity capital. Conducting their study on a large international sample of 16,334 firm-year observations across 39 countries between 2002 and 2013, they found that investing in CSR reduces the cost of capital in countries where investor protection is strong. In countries where investor protection is weak, managers tend to overinvest in CSR activities, which consequently increase the cost of equity capital. Thus, country-level investor protection acts as a moderator variable for the relationship between CSR and cost of equity.

Following the arguments presented, it can be inferred that good CSR performance by a firm may reduce its total risk. It may succeed in reducing its cost of equity capital if the lower risk is appreciated by analysts and investors and it benefits from a lower risk premium.

2.8 The Government of India and CSR

To foster adoption of best practices in corporate governance and CSR, in 2009, the Government of India issued guidelines, which listed ‘six core elements’ for companies. The six core elements are: (i) care for all stakeholders; (ii) function ethically; (iii) respect workers’ rights and welfare; (iv) respect human rights; (v) respect environment; and (vi) undertake activities for economic and inclusive development. Reporting CSR activities was also emphasized upon and it was suggested that companies need to report their CSR activities through their websites, annual reports and any other suitable communication channel (2009). For implementation of the CSR activities, the guidelines also suggested partnering with local authorities, business associations and civil society, allocating specific budgets for CSR expenditure, and engaging with fora and other businesses to encourage CSR activities.

In 2011, the 2009 CSR guidelines were replaced by the National Voluntary Guidelines on Social, Environmental and Economical Responsibilities of Business issued by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India in partnership with the Indian Institute of Corporate Affairs. The new guidelines were formulated considering the feedback on the 2009 CSR guidelines and advised companies to adopt the triple bottom-line approach, wherein its financial performance could be consistent with the societal and environmental expectations along with those of the stakeholders in a sustainable mode. The six core elements of the 2009 CSR guidelines were augmented into nine principles (2011), which are:

- Businesses should conduct and govern themselves with ethics, transparency and accountability

- Business should provide goods and services that are safe and contribute to sustainability throughout their life cycle

- Businesses should promote the wellbeing of all employees

- Businesses should respect the interests of, and be responsive towards all stakeholders, especially those who are disadvantaged, vulnerable and marginalized

- Businesses should respect and promote human rights

- Business should respect, protect, and make efforts to restore the environment

- Businesses, when engaged in influencing public and regulatory policy, should do so in a responsible manner

- Businesses should support inclusive growth and equitable development

- Businesses should engage with and provide value to their customers and consumers in a responsible manner

The guidelines of both 2009 and 2011 advised firms to integrate CSR into their business strategies and they should be concerned with the natural and social issues. While the 2009 guidelines did not make CSR a mandatory compliance requirement, the 2011 guidelines gave voice to the growing demand to make CSR mandatory. The Standing Committee of Parliament on Finance examined the Companies Bill of 2009 and recommended CSR spending to be made mandatory, which gave birth to the Section 135 of the Companies Act, 2013.

2.8.1 The Companies Act, 2013

In India, the concept of CSR is regulated by Clause 135 of the Companies Act, 2013, which was passed by both Houses of the Parliament, and received the approval of the President of India on 29th August, 2013. The CSR provisions within the Act are applicable to companies with an annual turnover of 1,000 crore INR and more, or a net worth of 500 crore INR and more, or a net profit of five crore INR and more. The new rules, applicable from the fiscal year 2014-15 onwards, also require companies to set up a CSR committee comprising of their board members, including at least one independent director (Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India, 2016).

The Act encourages companies to spend at least 2% of their average net profit in the previous three years on CSR activities. The Ministry’s draft rules, which have been offered inviting public comment, define net profit as the profit before tax as per the books of accounts, excluding profits arising from branches outside India. The Act lists out a set of activities[1] eligible under CSR. Considering the local conditions, companies may execute following board approval. The indicative activities which can be undertaken by a company under CSR have been specified under Schedule VII of the Act.

The draft rules (as of September 2013) provide a number of clarifications and while these are awaiting public comment before notification, some the highlights are as follows:

- Surplus arising out of CSR activities will have to be reinvested into CSR initiatives, and this will be over and above the 2% figure

- The company can implement its CSR activities through the following methods:

- Directly on its own

- Through its own non-profit foundation set-up so as to facilitate this initiative

- Through independently registered non-profit organisations that have a record of at least three years in similar such related activities

- Collaborating or pooling their resources with other companies

- Only CSR activities undertaken in India will be taken into consideration

- Activities meant exclusively for employees and their families will not

qualify - A format for the board report on CSR has been provided which includes amongst others, activity-wise, reasons for spends under 2% of the average net profits of the previous three years and a responsibility statement that the CSR policy, implementation and monitoring process is in compliance with the CSR objectives, in letter and in spirit. This has to be signed by either the CEO, or the MD or a director of the company (Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India, 2016).

In February 2014, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) published the Companies (Corporate Social Responsibility) Rules, 2014 (February, 2014) which stated that programs which only benefitted the employees and their families would not be considered as CSR. In June 2014, the MCA further clarified that one-off events and expenses incurred in compliance with statutes and legislations were excluded from CSR (June, 2014). Unfortunately, this attitude of heavily regulating CSR created more problems than solving due to the uncertainties arising from lack of clarity in the regulation. In addition, companies may formulate various structures which may have to be approved by the regulators and in their ensuing conflict with the latter, the focus may shift away from their responsibility of benefitting the society (Majumdar A. B., 2014).

The Government of India had made a series of announcements regarding the CSR legislation as it wavered between making CSR spending either voluntary or mandatory for the large Indian firms. The timing of these announcements provides a perfect background to gain insights into the effect that CSR expenditures are envisaged to have on the long-term success of Indian companies. Each announcement offered information that is expected to change expectations associated with future levels of CSR expenditures. Consequently, by examining the influence that these announcements have on the share prices of the firms, valuable insights can be gained about investors’ comprehension of the impact that CSR expenditure would have on the future profitability of a business.

While the practice of CSR in India is still confined within the philanthropic space, the focus has shifted from institutional building (educational, research and cultural) to community advancement through diverse projects. CSR is increasingly getting strategic in nature due to global influences and increasing levels of awareness of communities. Consequently, more and more companies are reporting their CSR activities in their official websites, sustainability reports, annual reports and some are even publishing their CSR reports (Pricewaterhouse Coopers India, 2013).

The Companies Act, 2013 has brought the notion of CSR to the forefront and via its disclose-or-explain decree, is advocating higher transparency and disclosure. The Schedule VII of the Act, which lists out the CSR activities, recommends communities to be the pivot. Simultaneously, the draft rules propose that CSR needs to be extended beyond communities and philanthropy while considering a company’s relationship to its stakeholders and integrating CSR into the core operations. Only time will tell how the concept of CSR is expanded in the country and is transformed into substantial action at the ground level.

2.9 Development of CSR in India

Sundar (2000) divided the development of CSR in India can be divided into four main phases:

First Phase: CSR Motivated by Charity and Philanthropy (1850 – 1914)

The first phase of CSR was predominantly defined by culture, religion, family tradition and industrialization. Prior to the 1850s, merchants committed their wealth to society for religious causes, for example, by building temples. The merchant class in the pre-industrialized India performed an important role in laying the foundations of philanthropy in the society. They constructed and sustained educational and religious organizations, social infrastructures, and made donations from their treasuries during hours of need (Sundar, 2000). Religious airs exemplified these charitable attempts, and were often confined to members of the same caste. Things changed for the better at the turn of the 19th century when these charities expanded to benefit all members of the society. The phrase ‘corporate social responsibility’ or CSR did not exist at that time and a company’s involvement in the social facets was considered as philanthropy. Especially, throwing the warehouses of food and treasure chests open during difficult times (such as famines or epidemics) were common practice (Arora & Puranik, 2004). Under the British colonial rule, the Western style of industrialization reached the Indian shores and changed the concept of CSR from the 1850s onwards. In the 19th century, the pioneers of industrialization in India were the businesses owned by the families such as Tata, Birla, Bajaj, Lalbhai, Sarabhai, Godrej, Shriram, Singhania, Modi, Naidu, Mahindra and Annamali, who were passionately dedicated to philanthropically motivated CSR (Mohan, 2001).

Second Phase: CSR for India’s Social Development (1914–1960)

The second phase of Indian CSR (1914–1960) was marked by the country’s fight for independence and was inspired primarily by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s theory of trusteeship, whose aim was to consolidate and amplify social development. During the freedom struggle, Indian businesses actively engaged in the reform process and participated in institutional and social development, since they considered the nation’s economic development as a means of protest against the colonial regime. Not only did companies see the country’s economic development as a protest against the colonial rule, they also participated in its institutional and social development (India Partnership Forum, 2002). The corporate sector’s engagement was driven by their vision of a modern and free India. M. K. Gandhi pioneered the concept of trusteeship in order to make the firms the ‘temples of modern India’. Business houses (particularly the well-established family businesses) founded trusts for schools and colleges and started training and scientific institutes (Mohan, 2001). The chiefs of the companies principally aligned the activities of their trusts with Gandhi’s reform programmes, which included activities that pursued, particularly, the abolition of untouchability, promoted women’s empowerment and rural development (Arora & Puranik, 2004). A strong patriotic element was evident among the philanthropic practices, and many of the forthcoming and eminent business leaders backed the causes of social reforms, poverty alleviation, women empowerment, caste systems, etc. (Sundar, 2000).

India gained its independence in 1947 and building a strong industrial foundation, while fostering the Indian cultural traditions, became the socio-political objective. This resulted in a highly centralized economy, which witnessed a fast growth in capital-intensive manufacturing facilities (Davies, 2002). As a result, by the end of the 1960s, the Indian economy found itself in an era of concentrated growth and protectionism for the domestic industries, while the Government undertook many social responsibilities (Nag, Ganesh, Pathak, & Sharma, 2003). Researchers like Kumar et al. (2001) call this ‘Nehruvian Statism’, after India’s first premier Mr. Jawaharlal Nehru, who was responsible for the introduction of this practice.

Third Phase: CSR under the Paradigm of the ‘Mixed Economy’ (1960–1980)

The third phase of CSR in India witnessed the rise of ‘mixed economy’, with the emergence of public sector undertakings (PSUs) and introduction of laws on labour and environmental standards. During this time period, corporate self-regulation shifted to strict legal and public regulation and the role of the private sector declined. The private sector was subjected to strict legal and public regulation under the new paradigm of ‘mixed economy’ (Arora & Puranik, 2004). The increased support for domestic industries also led to a focus on maximizing profits, which prompted many companies to resort to corruption and unethical practices. Consequently, the government was compelled to implement tougher regulations on corporate governance, labour and environmental issues (Sundar, 2000). In the following decade, industrial pollution control measures were introduced, which paved the way for the emergence of the first set of environmental regulations (Sawhney, 2003). Much to the disappointment of the proponents of ‘mixed economy’, the public sector met with limited success in effectively tackling development challenges and thus, the onus on the private sector grew for socio-economic development of the country (Ghosh, 2015).

Fourth Phase: CSR at the Interface between Philanthropic and Business Approaches (1980 onwards)

The fourth phase (1980 until the present) witnessed Indian companies and stakeholders taking a departure from the traditional philanthropic outlook and integrated CSR into the core operations of their businesses. It was during this time that CSR was being seen as an integral part of the coherent and sustainable business strategy. The Indian government started the process of modernization of the economy in the early 1990s by adopting liberalization, privatization and globalization (LPG) to integrate India into the global market. The Indian economy received the much-needed thrust towards development, the essence of which still persists today (Arora & Puranik, 2004). The philanthropic accomplishments of Indian businesses also increased due to increased ability to donate, keeping pace with the increasing expectations of the pubic and the government. It was not long before the Indian companies realized that they needed to comply with the international standards in order to compete globally and this led them to adopt the modern approach with the underlying objective of doing all that they could do and simply not some good to the society. This was indeed a win-win situation both for the society and the business, since the latter would succeed in creating a good reputation if it sincerely undertook benevolent activities to better the lives of many (Ghosh, 2015).

2.10 Studies on CSR in India

In spite of existence of differences in perceptions, operationalization and expectations of CSR practices with those of the developed nations, interest in CSR has been steadily gaining importance in India ( (Kumar, Murphy, & Balsari, 2001); (Mohan, 2001)). Most of the Indian companies regard CSR as philanthropy and not an integral part of their core strategies and hence do not expect any financial return for their CSR endeavours (Arora & Puranik, 2004). Hence, CSR is yet to gain on popularity in the Indian business psyche (Ghosh, 2015).

Research on CSR in India can be classified into four broad types, viz., studies which have been largely limited to self-reported questionnaire surveys [ (Atkinson & Khan, 1987); (Krishna, 1992); (Jain & Kaur, 2004)], focussing on the nature and properties of CSR [ (Arora & Puranik, 2004); (Pachauri, 2004); (Sood & Arora, 2006); (Singh S. , 2010)], those concentrating on the strategies and procedures of CSR [ (Arora & Rana, 2010); (Gupta & Saxena, April, 2006)] and directed towards the competitive advantage inferences of CSR [ (Sen, 2006); (Kansal & Joshi, 2014)].

The economic reforms pursued by India and its subsequent development as an emerging market and a major global commercial player have failed to make substantial change towards the perception of CSR ( (Kumar, Murphy, & Balsari, 2001); (Ruud, 2002); (Arora & Puranik, 2004); (Waldman, et al., 2006); (Husted & Allen, 2006); (Jamali & Mirshak, 2007). Most of the Indian companies focus solely on how to conduct CSR and have adopted only a handful of aspects of the global CSR plan instead of adopting it in its entirety (Ghosh, 2015).

Studies conducted on CSR in emerging economies like India rely on disclosure of CSR pursuits of companies. Chambers et al. (2003) found evidence that penetration of CSR reporting in India was the highest amongst the seven Asian countries, with 72% of the 50 largest Indian companies reporting their CSR activities, only 2% produce dedicated CSR reports. While studying the extent of CSR reporting, they direct to Maitland’s (2002) observations that there exists a high probability of the CSR reports to contain insignificant information.

The first attempt to study CSR in India was made by Singh and Ahuja (1983), where they studied 40 Indian public sector units (PSUs) during 1975-76 and concluded that only 40% of the firms disclosed about 30% of the total social disclosure items in their survey. Hedge et al. (1997) studied the annual report of Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL), one of the largest Indian steel manufacturing PSUs, for the year 1993 and found that the firm reported its social accounts – both social balance sheet and social income statement – as well as its human resources balance sheet.

In a more recent study on disclosure practices of Indian firms, Raman (2006) scrutinized the annual reports of the 50 largest companies to recognize the degree and quality of social reporting. The study found that product/service improvement and human resource development were emphasized in the CSR disclosures by the companies. However, since community development was not stressed upon by 29 companies from the sample, the study concluded that to a degree, Indian businesses do not consider community development as philanthropy any more. Hossain and Reaz (2007) studied the determinants of the extent of the voluntary disclosure practices of all the 38 listed Indian banks and concluded that only corporate size and assets-in-place are significant, while the other variables viz., age, diversification, board composition (represented by the percentage of non-executive directors), multiple-exchange listing and complexity of business, are insignificant.

A 2009 report by Karmayog, an online organization on CSR, challenged the idea that CSR in India was moving away from corporate philanthropy towards strategic CSR. It reported that despite 51% of Indian companies practise CSR, only 2% publish a separate sustainability report. The Emerging Markets Disclosure (EMD) Project of the US-based Social Investment Forum (SIF), Lessons Learned: The Emerging Markets Disclosure Project, 2008–2012, (2012) confirmed Karmayog’s report and found that amongst the emerging economies, Indian companies performed lowest in CSR disclosure and also in adhering to CSR standards and objectives.

Shankar and Panda (2011) conducted a content analysis of 40 Indian companies in 2006 and reported that qualitative statements dominated and declarative statements were marginalized in CSR reporting. Most companies reported extensively on their environmental contribution, while rural development and urban affairs were the least popular items in their CSR agenda. Almost in the same lines, Tewari (2011) employed content analysis to analyze the focus and intensity of CSR communication in annual reports of 100 IT companies and found that MNCs and the Indian companies differed in their outlooks of CSR. The MNCs lay more importance on work-life balance of their employees and product quality, while their Indian counterparts were more concerned with monetary benefits and product price. However, the Indian companies bettered the MNCs in their disclosures related to the environment, while the society as a stakeholder garnered the least attention.

Another study in CSR disclosure was done by Pahuja and Juneja (2013), where the researchers analysed the CSR disclosures by 30 Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) listed companies constituting the SENSEX by studying their annual reports for the financial year 2011-12. The study found that while all the companies made CSR disclosures in some form or the other, safety and healthcare and social accounting information were the most and least reported areas of disclosure. Jain and Winner (2016) studied the top and bottom 100 (i.e., 200 in total) Indian companies’ websites in March 2014, to analyse their CSR and sustainability reporting practices and evinced that while the top 100 companies prominently dispersed CSR information, the bottom 100 companies reported little or no information. The study confirmed Kim and Rader’s (2010) findings that large corporations are subject to more scrutiny from the public and media and hence are expected to contribute more towards the society compared to their smaller counterparts. The study also reported that the majority of the companies disclosed their commitment towards the environment, but remained silent on their impact on the environment. From a triple-bottom-line perspective, companies mostly focussed on economic impacts, which suggested that the focal point of this communication was to fortify the company’s market position and not to suggest its economic contributions.

Verma (June 2011) investigated the motivations and benefits of CSR schemes of Indian companies and found that long-term sustainability was the main motive behind adopting CSR practices. The companies aimed at creating a superior corporate image and goodwill, which would translate into higher customer loyalty and financial performance. The study also revealed a lack of awareness amongst the majority of the investors about the benefits of CSR since they solely concentrated on achieving high returns on their investments. Hearteningly, the study found a cluster of investors, however small, stayed invested in social responsible investing (SRI) funds for long time periods and did not expect any profits out of it.

A study by Bihari and Pradhan (2011), which linked CSR with financial performance of Indian banks found that the main objectives of CSR were image makeover, building relationships, accountability, maximizing gains, maximizing profits and long-term sustainability. The research found evidence that Indian banks improved their financial performance, corporate image and goodwill by increasing their CSR activities and suggested this to be a good example for other service sectors.

Mitra (2012) critically examined mainstream CSR discussion from the culture-centered approach (CCA) perspective. The study identified five main themes of CSR, viz., nation-building facade, underlying neoliberal logics, CSR as voluntary, CSR as synergetic, and a clear urban bias. The study concluded that despite CSR in India is meant for community and social benefit, the actual motive behind pursuing CSR was to increase profits, tap new markets and reduce expenditures.

Singh & Verma (2014) analysed the motive behind making CSR spending compulsory and suggested ways to strengthen the CSR model proposed by the Government of India (GoI). The study suggested that the GoI needs to present the real societal problems and also explain why companies must see it as a sustainable investment instead of an expense. The research further suggested tax incentives and formulation of a comprehensive CSR index to measure CSR performance of Indian companies.

Dhanesh (2015) analysed the drivers of CSR in India and based on 19 in-depth interviews with business leaders and senior managers of 16 companies from diverse industries, concluded that two contrasting perspectives dominated the understanding of CSR in India, viz., moral and strategic. A third perspective, which is formed primarily by a complex interaction of the moral and strategic perspectives, also was a key driver of CSR in India. The study revealed that most of the respondent companies were involved with CSR activities, like running schools and orphanages, battling child-labour, engaging in last-mile water and electricity connectivity problems and creating livelihood schemes.

Chandra & Kaur (2015) studied the CSR spends of the CNX Nifty 50 companies which represented about 66.85% of the free-float market capitalization of the stocks listed on National Stock Exchange (NSE) as on 30th June 2014. The study revealed that only 12 companies spend more than or equal to 2% of the average profits of the preceding three years and companies from the energy and power sector are the biggest spenders on CSR, while those from the pharmaceutical sector spend the least. Interestingly, the private sector firms spend on an average 1.31% of their profits, while the PSUs fall behind at 1.27% and only 1 PSU and 11 private sector firms are spending more than 2% of their average profits on CSR. Sadly, it also proved that on an aggregate, companies spend only 65% of the total mandatory CSR spend. The study further showed that the activities which dominated the companies’ CSR focus are education, healthcare, women empowerment, environment sustainability, infrastructure development and disaster relief.

Singh et al. (2015) developed theoretical and empirical linkages between CSR initiatives of Indian firms and their market development attempts at the bottom of the pyramid (BOP)[2]. Conducting qualitative in-depth interviews with 21 CSR heads of Indian firms, the study proposed five ways to make market development at BOP through CSR more effective. The study suggested making the BOP market development less risky, camouflaging the CSR program as a BOP pilot project to create internal adhesion within the firm, incorporating the BOP people with the last mile of the supply-chain of the firm, inviting government mediation to quicken scale-up and developing BOP as future markets for consumers and supply chain associates to increase the sustainability of the business.

Majumdar & Saini (2016) suggested a new paradigm of CSR, which extends beyond pure philanthropy. The study suggests ‘entrepreneurial orientation’, which has five dimensions viz., autonomy, innovativeness, risk-taking, pro-activeness and competitive aggressiveness, can be used by the firms to design innovative CSR schemes and implementation plans to gain unique strategic position. It noted that most of the CSR programs failed to generate the positive impact on society since they were merely used as marketing and communication tools by the companies. To address this issue, the study suggested involving the local community, which is the targeted beneficiary, at the CSR programs design phase.

Biswas et al. (2016) evaluated the contribution of CSR activities of Indian companies towards achieving inclusive growth in India. Applying content analysis of 42 non-financial firms’ annual reports, they found evidence that most of the CSR activities are in line with inclusive growth as envisaged by the GoI. The study revealed that companies were actively involved with providing livelihood opportunities either by employing members from the backward sections of the society or by imparting vocational training and making infrastructural support available for self-employment. The support thus extended by the companies in terms of education, health and community development, etc. not only benefitted the target groups, but also the entire nation.

Companies are facing newer challenges due to ever changing expectations from customers who are also becoming more and more concerned with their contributions to the society. Consequently, the companies are being pressurised to maintain transparency and be proactive in their public communications. Studies have shown that in addition to annual reports, websites are also being used as an effective and important channel of communication. However, since such research has been extremely few and far in between, how far Indian companies have succeeded in transparent and proactive communication of CSR activities still remains undecided (Ghosh, 2015).

A substantial amount of literature exists on studies conducted in the developed and industrialized nations regarding the pattern of CSR amongst the companies by studying the annual reports, stand-alone CSR reports and websites. However, with the exception of the cited literature, very little investigation in CSR in the Indian subcontinent has been carried out. The primary reason behind such a dearth of study may be attributed to the fact that there is no consensus between the companies and the regulators regarding what CSR actually encompasses. CSR by Indian companies range from providing lunch to employees to organizing marathons and collecting and donating funds to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or disaster relief funds. The GoI did not attempt to provide a comprehensive definition of CSR and instead made it a mandatory spend within stiff guidelines. As a consequence, very few investigations have been carried out to identify a pattern of CSR participation by the private sector companies of India.

References

(IBLF), I. B. (2003). Retrieved from http://www.iblf.org/csr/csrwebassist.nsf/content/g1.html

A Role for the Government – Issues at Hand, Kenan-Flagler Business School of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. (2003). Retrieved from Global Corporate Social Responsibility Policies Project: http://www.csrpolicies.org/CSRRoleGov/CSR_Issue/csr_issue.html

Ackerman, R. W., & Bauer, R. A. (1976). Corporate Social Responsiveness. Reston Publishing Co.

Arora, B., & Puranik, R. (2004). A review of corporate social responsibility in India. Development, 47(3), 93-100.

Arora, D., & Rana, G. A. (2010). Corporate And Consumer Social Responsibility: A Way Value Based System. Proceedings of AIMS International Conference on Value-based Management, (pp. 11-13).

Ashbaugh, H., Collins, D. W., & LaFond, R. (2004). Corporate governance and the cost of equity capital. Emory. Retrieved January 26, 2006

Asian Sustainability Rating. (2010, September). Sustainability in Asia: ESG Reporting Uncovered. Retrieved November 18, 2016, from http://www.sustainalytics.com/sites/default/files/sustainability_in_asia___esg_reporting_uncovered.pdf

Atkinson, A., & Khan, A. F. (1987). Managerial Attitudes to Social Responsibility: A Comparative Study in India and Britain. Journal of Business Ethics, 6, 419-432.

Azim Premji Foundation. (2016, November 17). Azim Premji Foundation About Us. Retrieved from Azim Premji Foundation: http://www.azimpremjifoundation.org/About_Us

Balakrishnan, R., Sprinkle, G. B., & Williamson, M. (2011). Contracting benefits of corporate giving: An experimental investigation. The Accounting Review, 86(6), 1887-1907.

Barnea, A., & Rubin, A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. Journal of business ethics, 97(1), 71-86.

Bassen, A., Meyer, K., & Schlange, J. (2006). The influence of corporate responsibility on the cost of capital. Available at SSRN 984406.

Benn, S., & Bolton, D. (2011). Key Concepts in Corporate Social Responsibility. London: Sage Publications.

Bihari, S. C., & Pradhan, S. (2011). CSR and performance: The story of banks in India. Journal of Transnational Management, 16(1), 20-35.

Bird, R., Hall, A. D., Momentè, F., & Reggiani, F. (2007, December). What Corporate Social Responsibility Activities Are Valued by the Market? Journal of Business Ethics, 76(2), 189-206.

Biswas, U. A., Garg, S., & Singh, A. (2016). Examining the possibility of achieving inclusive growth in India through corporate social responsibility. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 1-20.

Blazovich, J., & Smith, M. (2011). Ethical corporate citizenship. In C. Jeffrey (Ed.), Research on professional responsibility and ethics in accounting (Vol. 15, pp. 127-163). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Blowfield, M., & Murray, A. (2008). Corporate Responsibility: A Critical Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Botosan, C. A. (1997, July). Disclosure Level and the Cost of Capital. The Accounting Review, 72(3), 323-349.

Botosan, C. A. (2006). Disclosure and the cost of capital: what do we know? Accounting and Business Research, International Accounting Policy Forum, 31-40.

Botosan, C. A., & Plumlee, M. A. (2005). Assessing alternative proxies for the expected risk premium. The Accounting Review, 80(1), 21-53.

Brammer, S. J., Pavelin, S., & Porter, L. A. (2006). Corporate social performance and geographical diversification. Journal of Business Research, 59, 1025-1034.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007, October). The Contribution of Corporate Social Responsibility to Organizational Commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(10), 1701-1719.

Breuer, W., Rosenbach, D. J., & Salzmann, A. J. (2016, January 9). Corporate Social Responsibility, Investor Protection and Cost of Equity: A Cross-country Comparison. Available at SSRN.

Cajias, M., Fuerst, F., & Bienert, S. (2014). Can investing in corporate social responsibility lower a company’s cost of capital? Studies in Economics and Finance, 31(2), 202-222.

Campbell, J. Y. (1996). Understanding risk and return. Journal of Political Economy, 104(3), 298-345.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business horizons, 34(4), 39-48.

Chambers, E., Chapple, W., Moon, J., & Sullivan, M. (2003). CSR in Asia: A seven country study of CSR website reporting. (D. Matten, Ed.) International Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility Research Paper Series – ISSN 1479-5124.

Chandra, R., & Kaur, P. (2015). Corporate social responsibility spend by corporate India and its composition. IUP Journal of Corporate Governance, 14(1), 68-79.

Chava, S. (2010). Socially responsible investing and expected stock returns. Available at SSRN 1678246.

Claus, J., & Thomas, J. (2001). Equity premia as low as three percent? Evidence from analysts’ earnings forecasts for domestic and international stock markets. Journal of Finance, 1629-1666.

Claus, J., & Thomas, J. (2001). Equity premia as low as three percent? Evidence from analysts’ earnings forecasts for domestic and international stock markets. Journal of Finance, 56(5), 1629-1666.

Cochran, P. L., & Wood, R. A. (March 1984). Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance. The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 27, No. 1, 42-56.

Committee for Economic Development. (1971). Social responsibilities of business corporations. The Committee.

Dahlsrud, A. (2006, 2008). How Corporate Social Responsibility is defined: An Analysis of 37 Definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1-13.

Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: an analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management, 15(1), 1-13. doi:10.1002/csr.132

Davies, R. (2002, June). Corporate citizenship and socially responsible investment: Emerging challenges and opportunities in Asia. In unpublished paper delivered at the Conference of the Association for Sustainable and Responsible Investment in Asia, 10.

Deegan, C. (2000). Financial accounting theory. Roseville, NSW: McGraw-Hill.

Derwall, J., & Verwijmeren, P. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and the implied cost of equity capital. Working paper.

Dhaliwal, D., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2011). Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. The accounting review, 86(1), 59-100.

Dhaliwal, D., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2014). Corporate social responsibility disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The roles of stakeholder orientation and financial transparency. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 33(4), 328-355.

Dhaliwal, D., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2014). Corporate social responsibility disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The roles of stakeholder orientation and financial transparency. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 33(4), 328-355.

Dhanesh, G. S. (2015). Why corporate social responsibility? An analysis of drivers of CSR in India. Management Communication Quarterly, 29(1), 114-129. doi:10.1177/0893318914545496

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995, January). The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. The Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65-91.

Easton, P. D. (2004). PE ratios, PEG ratios, and estimating the implied expected rate of return on equity capital. The Accounting Review, 73-95.

Easton, P. D. (2004). PE ratios, PEG ratios, and estimating the implied expected rate of return on equity capital. The Accounting Review, 79(1), 73-95.

El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kim, H., & Park, K. (2014). Corporate Environmental Responsibility and the Cost of Capital: International Evidence. Available at SSRN 2467223.

El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kwok, C. C., & Mishra, D. R. (2011). Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital? Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(9), 2388-2406.

Fatemi, A., Fooladi, I., & Tehranian, H. (2015). Valuation effects of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Banking & Finance, 59, 182-192.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Financial Times Prentice Hall (1 Nov. 1983).

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. :. Boston: Pitman.

Friedman, M. (1970). The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. New York Times Magazine, 13, 32-33.

Friedman, M. (1971, September 13). The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. New York Times Magazine.

Gebhardt, W., Lee, C., & Swaminathan, B. (2001). Toward an implied cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 39, 135-176.

Gebhardt, W., Lee, C., & Swaminathan, B. (2001). Towards an implied cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 39(1), 135-176.

Ghosh, S. (2015). Is Corporate Social Responsibility in India Still in a Confused State?—A Study of the Participation of the Private Sector Companies of India in Corporate Social Responsibility Activities. Global Business Review, 16(1), 151-181.

Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Academy of management review, 30(4), 777-798.

Gompers, P., Ishii, J., & Metrick, A. (2003). Corporate governance and equity prices. Quarterly Journal of Economies, 118(1), 107-155.

Gordon, J., & Gordon, M. (1997). The finite horizon expected return model. Financial Analysts Journal, 52-61.

Goss, A., & Roberts, G. S. (2011). The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(7), 1794-1810.

Grayson, D., & Hodges, A. (2004). Corporate Social Opportunity! Seven Steps to Make Corporate Social Responsibility Work for Your Business. Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

Gregory, A., Tharyan, R., & Whittaker, J. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and firm value: Disaggregating the effects on cash flow, risk and growth. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(4), 633-657.

Gupta, D. K., & Saxena, K. (April, 2006). Corporate social responsibility in Indian service organisations: An empirical study. International conference on CSR agendas for Asia, 1314, p. 2006. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Guthrie, J., Petty, R., Yongvanich, K., & Ricceri, F. (2004). Using content analysis as a research method to inquire into intellectual capital reporting. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 5(2), 282-293.

Hail, L., & Leuz, C. (2006). International differences in the cost of equity capital: Do legal institutions and securities regulation matter? Journal of accounting research, 44(3), 485-531.

Harjoto, M. A., & Jo, H. (2015). Legal vs. normative CSR: Differential impact on analyst dispersion, stock return volatility, cost of capital, and firm value. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(1), 1-20.

Harjoto, M. A., & Jo, H. (2015). Legal vs. normative CSR: Differential impact on analyst dispersion, stock return volatility, cost of capital, and firm value. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(1), 1-20.

Harris, L. C., & Goode, M. M. (2004). The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust: a study of online service dynamics. Journal of Retailing, 80(2), 139-158.

Hegde, P., Bloom, R., & Fuglister, J. (1997). Social financial reporting in India: A case. The International Journal of Accounting, 32(2), 155-172.

Herremans, I. M., Akathaporn, P., & McInnes, M. (1993). An investigation of corporate social responsibility reputation and economic performance. Accounting, organizations and society, 18(7), 587-604.

Hillman, A. J., & Keim, G. D. (2001, February). Shareholder Value, Stakeholder Management, and Social Issues: What’s the Bottom Line? Strategic Management Journal, 22(2), 125-139.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. (2 ed.). Sage Publications.

Hopkins, M. (2007). Corporate Social Responsibility and International Development. Is Business the Solution? London: Earthscan.

Hossain, M., & Reaz, M. (2007). The determinants and characteristics of voluntary disclosure by Indian banking companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 14(5), 274-288.

Husted, B. W., & Allen, D. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in the multinational enterprise: Strategic and institutional approaches. Journal of International Business Studies, 838-849.

Indian Institute of Corporate Affairs. (2011). National Voluntary Guidelines on Social, Environmental and Economical Responsibilities of Business. Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India.

Infosys Foundation. (2016, November 17). Infosys Foundation Mission. Retrieved from Infosys.com: https://www.infosys.com/infosys-foundation/about/Pages/index.aspx

Introduction to Corporate Social Responsibility. (2000). Retrieved from Business for Social Responsibility: http://www.khbo.be/~ lodew/Cursussen/4eingenieurCL/The%20Global%20Business%20Responsibility%20Resource%20Center.doc

Issues in Corporate Social Responsibility. (2003a). Retrieved from Business for Social Responsibility: http://www.bsr.org/AdvisoryServices/Issues.cfm

Jackson, P., & Hawker, B. (2001). Is corporate social responsibility here to stay? Retrieved from www.cdforum.com: http://www.cdforum.com/research/icsrhts.doc

Jain, R., & Winner, L. H. (2016). CSR and sustainability reporting practices of top companies in India. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 21(1), 36-55.

Jain, S. K., & Kaur, G. (2004). Green Marketing: An Attitudinal and Behavioural Analysis of Indian Consumers. Global Business Review, 5(2), 187-205.

Jamali, D., & Mirshak, R. (2007). Corporate social responsibility (CSR): Theory and practice in a developing country context. Journal of business ethics, 72(3), 243-262.

Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency cost of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. American Economic Review, 76(2), 323-329.

Jensen, M. C. (2002). Value maximization, stakeholder theory, and the corporate objective function. Business ethics quarterly, 12(02), 235-256.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of financial economics, 3(4), 305-360.

Jo, H., & Harjoto, M. A. (2011). Corporate governance and firm value: The impact of corporate social responsibility. Journal of business ethics, 103(3), 351-383.

Jo, H., & Harjoto, M. A. (2012). The causal effect of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility. Journal of business ethics, 106(1), 53-72.

Kanji, R., & Agrawal, R. (2016). Models of Corporate Social Responsibility: Comparison, Evolution and Convergence. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 2277975216634478.

Kansal, M., & Joshi, M. (2014). Perceptions of investors and stockbrokers on corporate social responsibility: a stakeholder perspective from India. Knowledge and Process Management, 21(3), 167-176.

Kim, S., & Rader, S. (2010). What they can do versus how much they care: assessing corporate communication strategies on Fortune 500 web sites. Journal of Communication Management, 14(1), 59-80.

KPMG & ASSOCHAM. (2008, January 30). Corporate Social Responsibility – Towards a Sustainable Future (A white paper). Retrieved November 18, 2016, from KPMG: www.in.kpmg.com/pdf/csr_whitepaper.pdf

Krishna, C. G. (1992). Corporate Social Responsibility in India: A Study of Management Attitudes. India: Mittal Publications.

Kumar, R., Murphy, D. F., & Balsari, V. (2001). Altered images: The 2001 state of corporate responsibility in India poll. New Delhi: Tata Energy Research Institute.

Lee, D. D., & Faff, R. W. (2009). Corporate sustainability performance and idiosyncratic risk: A global perspective. Financial Review, 44(2), 213-237.

Lee, M.-D. P. (2008). A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: Its evolutionary path and the road ahead. International Journal of Management Reviews, 53-73.

Levitt, T. (1958). The dangers of social-responsibility. Harvard business review, 36(5), 41-50.

Maitland, A. (2002). How to Become Good in all Areas: Corporate Social Responsibility: CSR is Here to Stay-But It is Unfamiliar Territory for Most Managers’. London: The Financial Times.

Majumdar, A. B. (2014). India’s Journey with Corporate Social Responsibility-What Next? JL & Com., 33, 165.

Majumdar, S., & Saini, G. K. (2016). CSR in India: Critical review and exploring entrepreneurial opportunities. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Emerging Economies, 2(1), 56-79.

Marrewijk, M. V. (2003). Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: between agency and communion. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(2/3), 95-105.

Marrewijk, M. V. (2003). Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: between agency and communion. Journal of Business Ethics, 95-105.

Marrewijk, M. V. (2003). Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: between agency and communion. Journal of Business Ethics, 95-105.

Matthiesen , M.-L., & Salzmann, A. J. (2015). Corporate Social Responsibility and Firms’ Cost of Capital: Does Culture Matter? Available at SSRN 2600542.

McGuire, J. B., Alison Sundgren, A., & Schnee, T. (December 1988). Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Financial Performance. The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 31, No. 4, 854-872.

McGuire, J. B., Sundgren, A., & Schneeweis, T. (1988). Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance. Academy of management Journal, 31(4), 854-872.

Meehan, J., Meehan, K., & Richards, A. (2006). Corporate social responsibility: the 3C-SR model. International Journal of Social Economics, 33(5/6), 386-398.

Ministry of Corporate Affairs. (February, 2014). Companies (Corporate Social Responsibility Policy) Rules, 2014. New Delhi: Government of India.

Ministry of Corporate Affairs. (June, 2014). Clarifications with regard to provisions of Corporate Social Responsibility under section 135 of the Companies Act, 2013. New Delhi: Government of India.

Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India. (2009). Corporate Social Responsibility Voluntary Guidelines. Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India.

Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India. (2016, April 18). http://www.mca.gov.in/MinistryV2/companiesact.html. Retrieved from http://www.mca.gov.in: http://www.mca.gov.in/Ministry/pdf/CompaniesAct2013.pdf

Mirvis, P. (2012). Employee engagement and CSR. California Management Review, 54(4), 93-117.

Mishra, D. R. (2015). Post-innovation CSR Performance and Firm Value. Journal of Business Ethics.

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997, October). Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. The Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853-886.

Mitra, R. (2012). “My country’s future”: A culture-centered interrogation of corporate social responsibility in India. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(2), 131-147.

Mohan, A. (2001). Corporate citizenship: Perspectives from India. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 2, 107-117.

Nag, G. C., Ganesh, S. R., Pathak, R. D., & Sharma, B. (2003). Through the eyes of an insider: Case study of an MNC subsidiary in an emerging economy. Thunderbird International Business Review, 45(4), 481-491.

Nan, X., & Heo, K. (2007). Consumer Responses to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives: Examining the Role of Brand-Cause Fit in Cause-Related Marketing. Journal of Advertising, 36(2), 63-74.

Öberseder, M., Schlegelmilch, B. B., & Murphy, P. E. (2013). CSR Practices and Consumer Perceptions. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1839-1851.

Ohlson, J. (1995). Earnings, book value, and dividends in security valuation. Contemporary Accounting Research, 661-687.

Ohlson, J., & Juettner-Nauroth, B. (2005). Expected EPS and EPS growth as determinants of value. Review of Accounting Studies, 349-365.

Ohlson, J., & Juettner-Nauroth, B. (2005). Expected EPS and EPS growth as determinants of value. Review of Accounting Studies, 10(2-3), 349-365.

Oikonomou, I., Brooks, C., & Pavelin, S. (2012). The impact of corporate social performance on financial risk and utility: A longitudinal analysis. Financial Management, 41(2), 483-515.

Overview of Corporate Social Responsibility. (2003b). Retrieved from Business for Social Responsibility: http://www.bsr.org/BSRResources/IssueBriefDetail.cfm?DocumentID=48809

Pachauri, R. K. (2004, December 22). The rationale for corporate social responsibility in India. Retrieved from The Financial Express: http://www.teriin.org/upfiles/pub/articles/art46.pdf

Pahuja, A., & Juneja, S. (2013). Corporate Social Reporting in India: An Analysis of Bombay Stock Exchange Listed Companies. Corporate Social Responsibility: Conceptual Framework, Practices and Key Issues, 246-258.

Pearce, C. L., & Manz, C. C. (2011). Leadership Centrality and Corporate Social Ir-Responsibility (CSIR): The Potential Ameliorating Effects of Self and Shared Leadership on CSIR. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(4), 563-579.

Pirsch, J., Gupta, S., & Grau, S. L. (2007). A framework for understanding corporate social responsibility programs as a continuum: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(2), 125-140., 70(2), 125-140.

Prahalad, C. K. (2004). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: Eradicating poverty with profits. Philadelphia: Wharton Business Publishing.

Prahalad, C. K., & Hammond, A. (2002). Serving the world’s poor, profitably. Harvard business review, 80(9), 48-59.

Prahalad, C. K., & Hart, S. L. (2002). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. Strategy+Business, 26(1), 54-67.

Pricewaterhouse Coopers India. (2013). Handbook on corporate social responsibility in India. Gurgaon.

(2001). Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibilities. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

Raman, S. R. (2006). Corporate social reporting in India—A view from the top. Global Business Review, 7(2), 313-324.

Reverte, C. (2012). The impact of better corporate social responsibility disclosure on the cost of equity capital. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 19(5), 253-272.

Reverte, C. (2012). The impact of better corporate social responsibility disclosure on the cost of equity capital. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 19(5), 253-272.

Ruud, A. (2002). Environmental management of transnational corporations in India—are TNCs creating islands of environmental excellence in a sea of dirt? Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(2), 103-118.

Salama, A., Anderson, K., & Toms, J. S. (2011). Does community and environmental responsibility affect firm risk? Evidence from UK panel data 1994–2006. Business Ethics: A European Review, 20(2), 192-204.

Sawhney, A. (2003, January 4-10). Managing Pollution: PIL as Indirect Market-Based Tool. Economic and Political Weekly, 38(1), 32-37.

Schwartz, M. S., & Carroll, A. B. (2003). Corporate social responsibility: A three-domain approach. Business ethics quarterly, 13(4), 503-530.

Sen, S. K. (2006, December). Societal, Environmental and Stakeholder Drivers of Competitive Advantage in International Firms. Retrieved from SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1009991 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1009991

Shankar, A. N., & Panda, N. M. (2011). Corporate social reporting in India: An explorative study of CEO messages to the stakeholders. Zenith International Journal of Business Economics & Management Research, 1(3), 26-47.