Intangible Cultural Heritage around Jebel Elbarkal Archaeological Site

Info: 13114 words (52 pages) Dissertation

Published: 19th Nov 2021

Tagged: HistoryArchaeology

1. Introduction

The function of this section is to serve as a map of the Thesis, outlining the reason behind this research, what are the research problems, what are the aims of conducting this research and finally what are the research questions this thesis targets to answer.

1.1 Research problems and focus

The relation between the two components of cultural heritage, namely the tangible heritage and the intangible heritage, is intertwined and complex. It is difficult to draw a distinction between the two, as the tangible asset is part of cultural expression while the intangible heritage also needs physical manifestation. At present, there is, on the one hand, a lack of intensive action in integrating cultural heritage in its totality. On the other hand, the archaeological site as a tangible heritage aspect has met with an additional challenge, namely the lack of involving local communities and their conceptualisations, their assigned values and their interpretations of this heritage.

The goal of this research is to study the intangible cultural heritage of the local communities of the Merowe region associated with the Jebel Elbarkal World Cultural Heritage Site (WHC), particularly their oral history, oral literature, traditions, customs, story-telling and their cultural practices, to identify the cultural values and the ways of seeing to the archaeological sites of the region. Furthermore, since there are indications that the recent construction of the nearby Merowe Dam has altered both local lifestyles and relations to archaeological sites in the region (International Rivers ND) the project also aims to examine how the local communities experience their new way of life after the construction of the Merowe dam, through studying the intangible cultural heritage of the people around Jebel Elbarkal.

As an identity, self-identity formation and social reality always are embodied by and within a discourse which controls and is produced by cultural and social structures presented through intangible culture, this research intends to understand how the intangible culture of Jebel Elbarkal local communities provides them with a sense of identity. It is perhaps helpful in the first instance to point out that the concept of intangible cultural heritage this research applies refers to the oral tradition and history, oral literature, customs and beliefs and traditional games. These are practices which are not written down, but are passed orally from generation to generation and maintained in the present.

1.2 Aims and specific research questions

1.2.1 The purpose of the thesis

The purpose and importance of this research stem from the fact that it will be the first academic project that investigates the engagement of the local communities and their interpretation of the tangible cultural heritage in Sudan particularly, the archaeological site. The concept of communities’ relations in the academic discourse around Sudan cultural studies tends to end with many question marks and produces numerous discourses within official and unofficial heritage. This research project objects at answering some of these questions whilst analysing the implications of official and unofficial discourses. In addition to all of that, as a researcher coming from the same geographical, social and cultural background and moreover with experience living in the same area, I would like to employ my personal and my epistemological knowledge to have a well understanding of this phenomena. The intention is to suggest avenues for further study, to develop an operational guideline for Jebel Elbarkal heritage management and to assist archaeologists working on this site to deal effectively with the local communities as most of these archaeologists originate outside of this particular social and cultural context.

Moreover, the study will investigate the impacts of the Merowe Dam, also known as Merowe High Dam in Northern Sudan, which was built in the intended study area on the Nile’s fourth cataract (Figure 1) between 2003 and 2009. The dam created a reservoir with a length of 174 kilometres. It also displaced more than 50,000 people from the fertile Nile Valley to dry desert locations. Thousands of people who refused the vacation of their homes were flushed out by the expanding waters of the reservoir (International Rivers ND).

Figure 1: The Merowe dam location from Gebel Barkal

Source: Internationalrivers.org

The Dam has carried with it many social and environmental concerns, as it displaced many already socioeconomically vulnerable communities, putting strain on the social fabric of the area and, in the process, drawing our attention to issues of structural violence. The dam also flooded inestimable archaeological remains in its reservoir (International Rivers ND). This headed the local communities to refer to archaeological sites, including Jebel Elbarkal, as a cultural heritage in their resistance discourse (Askouri 2014). The dam meant a considerable social, cultural and economic change in local people’s lives as they resisted their displacement from the Nile valley, and proposed to be resettled along the banks of the new reservoir. The shifting of the geographical context for some of those local communities and the change of their lifestyle and cultural practice for those who decided to stay creates a significant need to examine and investigate the impact and the consequences of the Merowe dam on the social and cultural context of local communities, particularly their tangible and intangible cultural heritage.

1.2.2 Research Questions

To obtain a deep understanding of the topic under investigation and an awareness of the research problem, the following questions should be addressed:

First research question:

How are the local communities experiencing their new way of life after the construction of the Merowe dam?

First research question’s sub-questions:

- Has the Merowe dam produced a new way of life and accordingly a new intangible cultural heritage?

- Has Jebel Elbarkal local communities’ views and their relationship toward Jebel Elbarkal changed after the construction of the Merowe dam?

- Has the local communities’ resistance discourse impacted on their engagement with the archaeological site?

Second research question:

What is the intangible cultural heritage of the local communities associated with Jebel Elbarkal archaeological site and has this intangible cultural heritage influenced their relationship with this site?

Second research question’s sub-questions:

- What is the form of this intangible cultural heritage?

- Who are the local communities of the site?

- Are there any other local or national communities that claim association with this site?

- How can local communities engage with this site?

- What are the local communities’ engagement aspects towards Jebel Elbarkal? Is it collaboration, neglect or contestation modes and why?

Third research question:

How do the ethnic, gender, national and religious identities of the local communities associated with Jebel Elbarkal affect the nature of their relationship with the site in question?

Third research question’s sub-questions:

- Which kind of identities influence local communities’ engagement modes within this site, and why?

- What are the power of social, cultural, ethnical and political contexts and identities toward the local communities’ engagement?

- What identity dimensions are in operation within the local communities’ engagement process and modes?

- Is there any conflict of interest between those identities dimensions?

- What are the cultural meanings and the heritage values towards Jebel Ebarkal for each of these identities?

Fourth research question:

Does the landscape identity of Jebel Elbarkal provide the local communities with a form of identity?

Fourth research question’s sub-questions:

- What is the sense of place and sense of time attached to this place by the local community?

- What are the social and cultural representations that shape local communities’ identities formation within this site?

Fifth research question:

What is the politics of communities’ engagement, the power relations, cultural meanings and the significant values these factors represent and how are they embedded in the narrative discourse of the local communities of Jebel Elbarkal?

Fifth research question’s sub-questions:

- What are the forms of narrative produced, circulated, used and reused within local communities that have a connotation with Jebel Elbarkal archaeological site?

- Who is producing these narratives within local communities and how have they been circulated?

- What are the significant values and interpretations that are mediated and recreated by local communities regarding Jebel Elbarkal archaeological site?

- Do the local communities consider themselves as a stakeholder for this site?

- Do the local communities’ discourses have a power over the government’s Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD)?

- What is the reflection of AHD within the local communities’ narratives and discourse?

2. Research context

2.1 Introduction

This section sets the scene for this research; it has been divided into three parts. The first part introduces the study area and the local communities. The second part outlines the general academic discourse around Jebel Elbarkal archaeological site. The final part discusses the so-called outstanding universal values behind designation of the site as a World Heritage Site.

2.2 The study area and people

Debate within wide-ranging disciplines, remarkably anthropology and history has produced a rich body of research attempting to locate Sudan as a region of study, what has distinguished particularity from other parts of Africa. The distinction has its background in popular perception and views in politics that counted Sudan as characterised by Arab and Islamic identities. Historically, other names have been used to describe current Sudan region: “Kush” has been widely used as well as “Aithiopia”. To the Arabs, it was a part of what they named it “Bilad –Elsudan” (Edwards 2004:1).

Moving beyond, but closely connected with the focus research area for this project, is the concept of Nubia and Nubian people. This has been used to describe Egypt’s southern neighbour. While other forms of the name are recognised in many languages, since it first appears in classical sources, the term Nubia has been used to describe the areas of northern Sudan and southern Egypt.

The recent political boundaries of the Sudan region have the problem of defining the study area and the scale of analysis the region of Sudan has great challenges in terms of the multi-ethnic society in which there are ethnic groups continuously forming and reforming the creation of regional history (Edwards 2004). Although Sudan’s residents are divided by ethnic, linguistic, and religious variation, many Sudanese in the north the study area claim Arab origin and speak Arabic. Sudanese Arabs are highly differentiated. People who live in the Merowe region are one of the tribes that perceive and identify themselves as an Arab/Muslim social group within the whole of Sudan as an ethnically and linguistically plural society. Mainly they are agricultural people. Traditionally they have been strongly represented in the army, police, and border guards, while other tribes were involved in occupations such as spinning, weaving and transportation. The district around Jebel Elbarkal is occupied by the Shaigiya tribe, formed of mixed Arab and Nubian elements. These people evolved and settled here before the 14th century (Kendall 2010).

2.3 Jebel Elbarkal name, feature and landscape identity

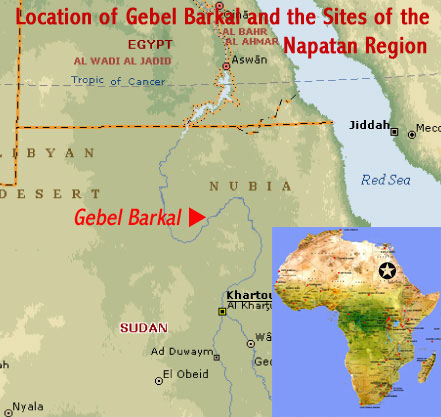

Jebel Barkal (“Mt. Barkal”) (var. Gebel Barkal, Gebel el-Barkal, and in several sources Gebel Berkel/Birkel, due to different transliterations of the name as rendered in Arabic letters. Jebel Elbarkal is in the western edge of Karima town, north Sudan, about 365 km NNW of Khartoum and 23 km downstream from the Merowe Dam at the fourth cataract of the Nile (Figure 2) (Kendall 2010).

Figure 2: Jebel Elbarkal Location and map. African World Heritage Sites.

23 km downstream from the Merowe Dam at the fourth cataract of the Nile.

Jebel Elbarkal’s most unique feature is Taharqa, the colossal free-standing pinnacle on the south corner of its cliff (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The cliff monument of Taharqa

© UNESCO

http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1073/gallery/ Author: Maria Gropa

This towering monolith was anciently seeming as a gigantic natural statue with many overlapping identities: a rearing uraeus serpent, a phallus, a squatting god (or several), depending on the direction from which it was seen (Kendall 2010). The mountain’s uncommon appearance (Figure 4) – its isolation, sharp profile, and spire-like pinnacle, 75 m high – made it a natural wonder in ancient times and excited intense theological speculation (Kendall 2010).

Figure 4: Jebel Barkal overview (https://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=i&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=images&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CAYQjB0&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ancientsudan.org%2Freligion_01_basics_kushite_religion.html&ei=o7yBVfj5OILfU8X-ibAL&bvm=bv.96041959,d.d24&psig=AFQjCNGLm2XmgiZ0RbnGW01_7FbrmaY5tA&ust=1434652183823646)

The structures and archaeological features and the landscape identity of Jebel Elbarkal are as follows:

- A Meroitic Palace (Figure 5)

Figure 5: A Meroitic Palace

Photographer. Mohammedani Ibrahim Ibrahim © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

http://www.jebElbarkal.org/frames/B100.pdf

- The temples to Hathor and Mut (Figure 6). Hathor and Mut were associated with each other and they were identified with a goddess called the “Eye of Re” (Jebelbarkal.org.ND).

Figure 6: The temples to Hathor and Mut

https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/10133167889070970/

- The cliff monument of Taharqa (Figure 3)

- The temple of Amun of Napata, Egyptian Phases

- The temple of Amun of Napata, Napatan and Meroitic Phases

- The reliefs of Piankhy program as it has been shown on the wall description.

- The statue cache (Figure 8)

Figure 8: The largest statue in the cache represented Taharqa wearing the crown of the god Shu.

Sudan National Museum, Khartoum (Photo by Enrico Ferorelli)

- The mammisi temple

- The enthronement pavilion

- The temple of Osiris-Dedwen

- The sub chapels

- The temple of Amun of Karnak at Napata

- “The Edifice of Piankhy”

- The Per-Wer (temple of Weret-Hekau)

- The Napatan Palace

- House of the High Priest of Amun

Jebel Elbarkal has five Archaeological sites, stretching over more than 60 km in the Nile valley. They are testimony to the Napatan (900 to 270 BC) and Meroitic (270 BC to 350 AD) cultures. Jebel Elbarkal has been strongly associated with religious traditions and folklore. The largest temples are still considered by the local people as sacred places (UNESCO 2003).

2.4 Jebel Elbarkal as a world cultural heritage site

Jebel Elbarkal and the Sites of the Napatan Region comprise a series of archaeological sites that are testimony to the important ancient culture of the Second Kingdom of Kush. The designated area of more than 60km length in the Nile Valley contains the following five locations (worldheritagesites.org ND):

1. Jebel Elbarkal: religious and administrative centre on a natural hill.

2. El-Kurru: cemetery and royal burial place.

3. Nuri: cemetery with pyramidal tombs.

4. Sanam: residential area and cemetery for common people.

5. Zuma: burial field.

Jebel Elbarkal was inscribed as a World Heritage Site (WHS) in 2003 (UNESCO.org ND). The so-called outstanding universal values motivating the designation of Jebel Elbarkal as a World Heritage Site (WHS) to be protected for the future generations is as follows:

- The pyramids, palaces, temples, burial chambers and funerary chapels of Jebel Elbarkal and the Sites signify a masterpiece of imaginative genius representing the artistic, social, political and religious values of a human group for more than 2000 years

- Jebel Elbarkal stands as an astonishing witness of the Napato-Meroitic (Kushite) civilization which had solid associations to the northern Pharaonic and other African cultures.

- Jebel Elbarkal typology buildings represent an outstanding example of funerary architecture and distinctive art that prevailed over a long period of time (9th Century BC- 4th Century AD).

Jebel Elbarkal has been strongly associated with religious traditions and local folklore. For this reason, the largest temples (Amon Temple for example) were built at the foot of the hill and are still considered by the local people as sacred places (UNESCO.org ND).

3. Literature Review

3.1 Introduction

The purpose of the review of the literature is to address the gap in the knowledge this research is intended to fill, as well as which issues, discourses and concepts are relevant to this research.

3.2 Understanding cultural heritage and intangible cultural heritage

The relevant key concepts that are significant for studying the intangible cultural heritage around Jebel Elbarkal archaeological site, which will be the focus of the literature review section of this study, are as follow: cultural heritage, intangible cultural heritage, communities’ engagement, identity, national identities, gender, ethnicity, discourse, sense of place, and sense of time. These concepts will assist on identifying the theoretical approach for examining the research question and offer direction in data collection structure, interpretation and analysing.

Heritage consists of cultural and social processes engaged with acts of remembering to generate ways of understanding and engagement with the present. Intangible and tangible cultural heritage are intertwined and complex. Acknowledging that, intangible heritage can be seen as a tool through which the tangible heritage could be interpreted, defined, produced, and transformed into a store of cultural and social values. More important each individual should be addressed well thought-out not in segregation but within its entire context of the relation between its tangible and intangible environment (Munjeri 2004:14).

Intangible cultural heritage has been defined by UNESCO in the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003) as “the practices, representations, expressions as well as the knowledge and skills that communities, groups and in some cases individuals recognise as part of their cultural heritage” (UNESCO 2003: Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage). The concept of intangible cultural heritage implies a transmitted nature that provides people with a sense of identity and continuity over generations (Kato 2006:460). In cultural heritage academic discourse the general definition offered for Intangible Cultural Heritage is in form of a list to include practice, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills, as well as instruments, objects, and artefacts and cultural aspects, while tangible and intangible cultural heritage is defined to mean those assets that have physical embodiment of cultural values, which include among others, building and historic places, monuments, books, works of arts and artifacts (UNESCO 2003: Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage). However, the separation between tangible and intangible cultural heritage has been contested among scholars as it is artificial and hard to establish in theory and practice (Munjeri, 2004). The cause behind this is the fact that the forms of heritage that we perceive as tangible are considered as heritage because of their socially created intangible value and meaning, not because of their physical nature. In other words, they originate from intangible forms of interests, ideas or desire to create them (Smith 2006).

3.3 Communities engagement

For understanding local communities’ engagement processes and modes of relationship within Jebel Elbarkal archaeological site, it is essential to define and conceptualize the communities which interact with this World Heritage Site through various methods. Cultural heritage studies literature has shown a wide-ranging set of terms used to address the communities in relation to archaeology and heritage. These include: communities’ archaeology, community-engaged, community-based and community-led, outreach, public archaeology, indigenous archaeology, communities collaboration, communities facilitation, postcolonial archaeology, public education, democratic archaeology, communities heritage, participatory archaeology and alternative archaeology (Smith and Waterton 2009:16). The interest of researching communities has its roots in the nineteenth century as a part of broader sociological fields (Smith and Waterton 2009:20). A general assumption has linked communities with locality and a geographically based factor. However, there are communities that define themselves more by their social and cultural experience and by their political views and aspirations. Within this study, the communities’ concepts refer to social groups which have a shared set of values, beliefs and interests. Among those social groups are the local communities around the archaeological site. Each of these communities has multiple purposes in the cultural meaning and interpretation process, as well as the management of heritage and heritage identities (Ashworth and Graham 2007). Local communities as stakeholders have knowledge that heritage can play a significant social function as part of the cultural context because it has a key role in shaping the historical memory of their society (Vienna 2014: 97).

3.4 Identity from a cultural heritage perspective

Identity and its impact within the context of this project refer to the ways in which markers such as: ethnicity; gender, nationality, religion and shared interpretations of the past are used to construct narratives of inclusion and exclusion that define communities (Graham and Howard 2003:5). By producing a set of symbols or lifestyle choices from which individuals make their own selections (Macdonald 2013:167), these symbols and sets can be connected to specific groups of people. Accordingly, the definition and meaning of identity is slippery, changeable and multi- dimensional. It can be a force for ‘defining and locating individuals in the world over the prism of the collective character and its distinguishing culture’ (Stephens Tiwari 2014:104). The ways in which people engage with cultural heritage depend upon the specific time and place and historical conditions. Furthermore, identity is fluid, subjective and multi-dimensional, as the sense of belonging centres not only on the ways we may (or may not) prompt and present our cultural identities and affiliations, but is also concerned with articulating and figuring out a range of other cultural, social and political experiences. These experiences may be structured and understood by relations defined, for instance, by ethnicity, by class, or by religious beliefs (or non-beliefs), by age, and/or by gender (Smith 2008:160). In his contribution, Stuart Hall shows how identities are formed and transformed continuously in relation to the ways individuals and groups are represented or addressed in the cultural systems (Hall et al., 1996: 597). In addition to that it depends upon factors such as their gender, age, class, and their economic situation (Bender 1993: 2)

3.4.1 Identity Levels, dimensions and boundaries

Three aspects of identity that will receive particular attention within this study are ethnicity, gender and national identity. In the last 30 years, words such as ethnic group, ethnic identity and ethnicity have become commonplace (Cornell and Hartmann 1998:15). Max Weber is the only one of the classical sociologist theorists to offer an explicit definition he term ‘ethnic’. He says “we shall call ethnic groups for those human groups that entertain a subjective belief in their common descent because of similarities of physical type or of customs or both (Weber 1986). Ethnic identity is a small fraction and are parts of the many identities mobilized in the politics of everyday life (Werbner 1996) and continues to shape contemporary heritage and the landscape of cultural elements more broadly (Litter 2008:89). Likewise, gender identity in terms of cultural practices, cultural knowledge and cultural power relation has momentous impact on communities’ engagement modes within heritage sites, particularly in the construction and expression of identity processes (Smith 2008:160). The research focus on these identity elements will be done through studying the interrelation between the productions, articulations, and representations of cultural heritage within this archaeological site.

National identity is one of the identities that can be expected to have an influence on shaping communities’ engagement modes with Jebel Elbarkal, as national identity provides an influential means of categorizing and connects a group of people to a geographic place (Duncan Light and Dumbraveanu 2007:28). The national culture is a discourse constructing meanings that influence and organize both people’s actions and conceptions of themselves as well as “the nation” within which they can identify (Hall et al., 1996:613). Countless buildings, monuments and landscapes have achieved substantial significance as symbols or icons of a developing nation, and have been appropriated for usage in nation building (Duncan Light and Dumbraveanu 2007:29). National identity and nationalism state the desire of people to establish and maintain a self-governing political entity. It has become one of the most powerful forces in the contemporary world (Cornell and Hartmann 1998: 34).

A sense of national identity is unquestionably central for many people’s life, feeling of belonging and identifying them with a particular group, and at the same time being dissimilar from other groups. One of the heritage values that have been embedded in archaeological sites is the political role of reinforcing the nation-building process and national identity. A nation is a symbolic community which produces a sense of identity and loyalty. The variances between nations lie in the different between which they are imagined (Hall et al., 1996:613). In fact, all communities’ greater than primordial village face to face interactions are imagined communities (Anderson 2006:6). These imagined communities are constituted by social memories, the desire to live together and the perpetuation of the heritage (Hall et al., 1996:616). The heritage works as an exporter of cultural meanings, a focus of identification, and a method of representation.

Major political change or the arrival of new socio-political forces within societies tends to be reproduced in fundamental or gradual transformations of the public landscape of memory. Subsequently, the existing heritage will be contested and the new order will attempt to legitimate itself over references to the past (Marshall 2008:347), particularly the one that represents the national identity and national culture. Not only the tangible cultural heritage forms, but likewise intangible aspects, such as names of the streets, public squares and historic sites, and even whole townscapes or natural landscapes. Societies recently emerging from previous colonial domination experiences, principally those which met violence in their colonial relationship and their political independence achievement, tend to be anxious about issues of representation and defining a new identity (Werbner 1996). In this process designated aspects of the past understood as a heritage serve as inspiration or foundation for their national identity (Marschall 2008:347).

Religious discourse as one of identity aspect produces meanings marked, shaped and exchanged through social interaction. These meanings further control and form the conduct and practices of individuals and social groups by helping them to determine rules, norms and conventions, which always change, from one culture or period to another (Ashworth and Graham 2007: 2). In case of Sudan archaeological sites the religious discourse institute the greatest powerful foundation to the social and political uses of these sites. The institutional Islamic discourse, as a religious dominant discourse in north Sudan along with local culture and local knowledge creates norms constrains people acts and behaviour. Accordingly, the power of this discourse played crucial roles in Jebel Elbarkal local communities in terms of their social structure, setting and customs as well as their cultural practice and values.

In addition to the previous identities dimensions, it is significant to understand the creation and management of place identities. Individuals and social groups have a sense of belonging to certain landscapes. Landscape from this point of view is a cultural image, a symbolic mode of representing, and a way of structuring or symbolising (McDowell 2008:39). These symbolic systems are created by people through their experience and engagement with the world around them, or even distant and half fantasised places (Bender 1993: 1). Acknowledging that, landscape can be read, interpreted and produced as a text, interacting with the social, economic and political institutions and context (Ashworth and Graham 2005:60). In examining how Jebel Elbarkal place identity provides its communities with a form of identity my view is that two crucial elements are at work. Notions of memory and notions of place. Memory and place via landscape are key transducers whereby the local, national and global are brought into mutual alignment (Stewart and Strathern 2003:3). Landscape identity has also been named as existential identity and does not only refer to the objects and the features of the physical landscape but also the associations, memories and symbolic meanings attached to the physical landscape (Stobbelaar and Pedroli 2011: 322). The investigation of landscape identity from this perspective is a comparatively new development (Taylor and Lennon 2012).

3.4.2 Identity, sense of place and sense of time

Within cultural heritage studies there are different concepts that focus on the different interpretations given to the surrounding physical environment and context. One of them is place attachment, through which individuals and communities form their self-identity. Place attachment refers to the positive affective bond or association between individuals or social and cultural communities with their residential environment as cognitive or emotional involvement and connection (Vong 2015:345). In examining the interrelation between Jebel Elbarkal as an archaeological site and its landscape identity, it is beneficial to study place attachment as an attitude toward it as a spatial setting, since this sense shares strong similarities with the affective and cognitive components of attitude, respectively (Jorgensen and Stedman 2001:233). In addition to that, the concept of sense of place can also be applied to this study. Sense of place describes a link between individuals and a certain setting, in which they see the place as a centre of meaning assigned by individual or groups to the landscape they engage with (Jorgensen and Stedman 2001: 233). Place attachment and sense of place as a concept share very strong associations with each other when tested empirically. Sense of place is a multidimensional connection between place and individuals through memories. On a personal level, individuals can become extremely attached to places in a mode that is critical to their well-being. Whether certain places are conserved, transformed or destroyed can be a crucial matter for the maintenance of their memories and sense of identity (Teather and Chow 2010:93).

3.4.3 Social Memory and Intangible Heritage transmission

Intangible Cultural Heritage itself is a memory, including the power of the process to preserve, transmit and accumulate this heritage within the human society (Petrov 1989: 78). The information preserved in the memory of the communities through oral tradition and intangible culture can be varied in nature. A specific kind of information I would like to focus on within this study is the awareness of past events relevant to the life of the Jebel Elbarkal local communities and their desire to symbolize these events in the Jebel Elbarkal site. The earliest explorer of the social framework of memory concepts was the French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs in the 1920s. Halbwachs argued that memory is constructed by social groups, who determine what is memorable and also how it will be remembered (Halbwachs 1996). In his contribution Halbwachs made a sharp distinction between collective memory, which was a social construct, and written history, which he considered in somewhat old fashioned positivist way to be objective. Furthermore, he treated memory as the product of social groups (Burke 1989: 98). All societies desire to represent memory through certain places that constitute significant sites invested with meaning to represent the heritage of an individual, group or communities (McDowell 2008:38). Accepting that heritage is a selective practice which uses the past as a resource for the present and future, it should be little surprise to find that memory and commemoration are extremely connected to the heritage process. The past in this sense is materialised in bodies, things, buildings and places (Hardy 2013:80).

3.4.4 Local communities and their conceptualisations of the tangible heritage

The role and heritage values of tangible cultural heritage are central to the way that communities engage with it. – Particularly in terms of its relationships with identity, dominant ideologies and the extent to which it is integrated with other social phenomena such as leisure, professionalization, contestation and lived culture (Waterton and Watson 2016:14). As a result of power relations and conflicts of interest among communities, a narrative that is embedded as a discourse has been produced and attached to heritage sites by each of their communities to support their sense of place. These narratives are mediated by their social and physical environment in which they emerge and, in turn, people make sense of their environment by drawing on collective memory or narrative as cultural tools to establish their communities’ meaning of a place (Stephens 2014:422). However, the local communities will have formed narratives that have a separate existence from those of the professionals who encounter them (Greer 2010). These narratives as oral traditions and local knowledge are powerful ways in which local communities have understood their environment and have structured their view to this site (Stephens 2014:415). Cultural heritage scholars have discussed how shared narratives and customs support the formation of certain identities and the claim of certain discourses. This narrative has been told and retold in histories, literatures, media, and popular culture through a set of stories, images, landscapes, scenarios, cultural symbols and ritual to represent shared experiences (Hall et al., 1996).

The discourse that is embedded within this narrative does not simply refer to the use of words or language, but rather to a form of social practice, social meaning, forms of knowledge, power relations and ideologies that are produced and reproduced via language to frame concepts, constitute and regulate understanding, mediate and construct the debate (Smith 2006:4). In other words, it is important who does the talking, and what largely unspoken rules govern what can be said, about what and by whom (Carman 2002:1). All societies shape a distinguishing social space with associated discourse to play a significant role for diffusing cultural values and for upholding cultural identity from one generation to the next (Teather and Chow 2010:93). This is important to the knowledge production process via systems and criteria of inclusion and exclusion (Carman 2002:1).

4. The Conceptual Framework and Research Methods

4.1 Introduction

This section outlines the conceptual foundation underlining the methodological framework which will be used to direct the collection and interpretation of data, as well as the different disciplines and theory that can be integrated within the study.

4.2 Research Method and design

This thesis is based on a qualitative research design. The collected data will be analysed by applying discourse analysis. A qualitative research methodology as an investigation means and style has become progressively more significant to researchers who are concerned about social and cultural context that construct people lives and the way they understand their world (Merriam 2009: 6). Qualitative researchers are attracted to understanding the way people interpret their own experiences, construct their world and produce their meaning according to their social and cultural constructions (Patton 1990). The benefits of applying quantitative method to this thesis will assist in: Firstly, identifying the intangible cultural heritage around Jebel Elbaral as this is the first research attempting to investigate the local communities around this heritage site. Secondly, qualitative research will allow the researcher to highlight and study the social and cultural context, knowledge and the way they understand and value of their past.

The research methodology will rely on an ethnographic approach to study the local communities of Jebel Elbarkal and their beliefs, attitudes, material culture, customs, and social interactions (Angrosino 2006: 1). The process of collecting material will be carried out mainly through observations, interviews, and focus groups. Since the primary data will be oral in nature (oral history and literature), the study will apply the methods of discourse analysis in interrogating, interpreting and evaluating the data. There are in fact many techniques employed to collect data in the course of ethnographic fieldwork. Acknowledging the fact that no data collection technique is without its limitation, this research aims to apply multiple techniques in the fieldwork to contribute to the information of people around Jebel Elbarkal; their way of life, oral history, oral literature and their believes. The appropriate way of doing so is to have prepared semi-structured interviews with the local oral historians and story-tellers as well as the communities’ leaders around this archaeological site (appendix figure10). This should go a long side with focus groups and observation techniques. Likewise, one of the major purposes of this research is to achieve in depth understanding of how people make sense of their lives and describe the process of making meaning to interpret their experiences.

Acknowledging that the primary data is an oral material, discourse analysis will be the chosen method of analysis. In attempting to apply discourse analysis on studying the intangible heritage of the local communities around Jebel Elbarakal, it may be useful to define what discourse is. The discourse is a “particular form of language with its own rules and conventions and the institution within which the discourse is produced and circulated” (Rose 2001: 36). Moreover, discourse is a form of knowledge produced through social interaction process to construct reality, be responsible for identity formation, rationalise attitudes and inspire values (Brown 1983). Therefore, discourse jointly is a source and a product of this knowledge (Barbara 2007). Intangible cultural heritage is one of the ways of expressing discourses structured according to various patterns of speech when people engage in different domains of social acts. Discourse is a specific way of speaking about and knowing the world (Jorgensen and Phillips 2002:17).

Accordingly, discourse analysis is a study of language (Jones 2012: 2). As language is a communication mode produced, circulated and used within semiotic systems (Barbra 2007 :2). This discourse reflect and represent the reality as it has been socially and culturally constructed by a powerful social institutions (Gill 1996:17), through which individual shape their acts and construct their identities (Jones 2012: 38). Despite the fact that discourse analysis serves numerous interdisciplinary approaches, it specifically signifies effective theories and methodologies for linguistics, communications and cultural studies (Jorgensen and Phillips 2002: 2). Among many approaches to discourse analysis I found that Foucauldian Discourse Analysis (FDA) can contribute effectively to interpreting the role of the intangible culture heritage around Jebel Elbarkal on the local communities’ conceptualisation to this site.

4.3 Ethics and research permits

To conduct research with the local communities around Jebel Elbarkal, researchers do not require permission from regional or national authorities in Sudan. However, this project requires an ethical approval from the University of Birmingham since all research within the University is required to go through the appropriate research ethics review process. This research will be bound by the stipulations of the Ethical Review Committee within the purview of which it falls.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this ethnographical qualitative research project is planning to gather and collect the intangible cultural heritage of the Merowe region’s local community. Observation, interviews and focus group techniques will be the essential primary data collecting methods. The aim of this research is to investigate and study the intangible cultural heritage of the local communities living in Merowe region, particularly their oral history, oral literature, traditions, customs, story-telling linked and their cultural practice associated to Jebel Elbarkal. The thesis intends to identify the cultural values and the way of seeing of these local communities toward Jebel Elbarkal archaeological sites of this region. Furthermore, it aims to investigate the process through which local communities give meanings to and interpreting the material of the past; in this case, the archaeological sites in Jebel Elbarkal.

Bibliography

Anderson, B. (2006) Imagined communities. 2nd edn. Verso. London and New York: Verso.

Angrosino, M. (2006) Doing cultural anthropology: Projects for ethnographic data collection. Waveland Press. [Online] available from <http://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=tEHmDG0CFsoC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=info:J_6Oez3iKYQJ:scholar.google.com&ots=HgOwE-w9DN&sig=rqLRdmA1NPSIfpBRCthqDqgu274&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false> [20 June 2016].

Ashworth, G.J, Graham, B. and Tunbridge, J.E. (2007) Pluralising Pasts, Heritage, Identity and Place in Multicultural Societies. London: Pluto Pres.

Askouri, A. (2014) Merowe Dam A Case for Resistance to Displacement. The Seventh International Workshop on Hydro Hegemony. London: Available at: https://www.uea.ac.uk/documents/40159/5624523/HH7+-+Askouri+-+The+Merowe+Dam+A+Case+of+Resistance+and+Activism+against+Forced+Displacement.pdf/1e907036-85a2-4a63-89a2-f259e586fab7 (Accessed: 18 March 2017).

Assmann, J. and Czaplicka, J (1995) Memory and Cultural Identity. New German Critique, Duke University Press. No. 65. 125-133.

Barbara, J. (2007) Discourse analysis. 2nd ed. Oxford: Black well publishing.

Bender, B. (1993) Introduction: Landscape – Meaning and Action. Landscape Politics and Perspectives Oxford: Berg publishers.

Bender, B. (1993) Landscape Politics and Perspectives. Oxford: Berg publishers.

Beneki, E., Delgado, J. and Filippoupoliti, A. (2012) Memory in the maritime museum: objects, narratives, identities. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 18:4, 347-351. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxye.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527258.2011.647861?need Access=true [Accessed 19 September 2016].

Biehl, P.F. (2014) Identity and Heritage: Contemporary Challenges in A Globalized World. [online] Available from: http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxye.bham.ac.uk/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzg3MDA3OF9fQU41?sid=9bba69fc-87d4-4a09-b2f7-25da00b5a0d2@sessionmgr107&vid=0&format=EB&rid=1 [Accessed 09 May 2016]

Borona, G and Ndiema, E. (2014) Merging research, conservation and communities engagement Perspectives from TARA’s rock art communities projects in Kenya, Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development. 4: 2. 184-195. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [online] Available from: http://www.emeraldinsight.com.ezproxye.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdfplus/10.1108/JCHMSD-04-2013-0012 [Accessed 10 January 2017].

Breen, C, Reid, G and Hope, M. (2015) Heritage, identity and communities engagement at Dunluce Castle, Northern Ireland. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 21:9, 919-937. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527258.2015.1035737 [Accessed 17 June 2016].

Brown, J. (1983) Discourse analyses. Cambridge University Press. [Online] available from: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=9gUrbzov9x0C&printsec=frontcover&dq=discourse+analysis+Gilian+Brown&hl=en&sa=X&ei=ZCxdU-2nDbDo7Aaa0IBw&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=discourse%20analysis%20Gilian%20Brown&f=false f> [24 November 2016].’

Buiek, K and Juul, K. (2008) ‘We Are Here, Yet We Are Not Here’: The Heritage of Excluded Groups. The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. Ashgate publishing limited. Surrey. England. Ashgate publishing Company. Burlington. USA.

Burke, P. (1989) ‘History as social memory’in Butler, T Memory history, culture and mind. Network: First Blackwell ltd. pp97- 113

Carman, J. (2002) Archaeology and Heritage, an Introduction. London and New York: Continnum.

Carman, J. (2003) Against Cultural Property, Archaeology, Heritage, and Ownership. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd.

Chirikure, S., Manyanga, M., Ndoro, W. and Pwiti, G. (2010) Unfulfilled promises? Heritage management and communities participation at some of Africa’s cultural heritage sites, International Journal of Heritage Studies.16:1-2, 30-44. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250903441739?needAccess=true [Accessed 19 October 2016].

Cornell, S and Hartmann, D. (1998) Ethnicity and race, making identities in changing world. Thousand Oaks, London and New Delhi: Sage Publication Company.

Crooke, E. (2010) The politics of communities heritage: motivations, authority and control. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 16:1-2. 16-29. Routledge Taylor & Francis group: [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250903441705?needAccess=true [Accessed 22 0ctober 2016].

Denzin, N and Lincoln, L. (2005) The sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. London. California. New Delhi: Sage.

Duncan Light, D. and Dumbraveanu, D. (2007) Heritage and national identity: Exploring the relationship in Romania. International Journal of Heritage Studies.3:1, 28-43. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxye.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527259708722185 [Accessed 22 January 2017].

Edwards, D. (2004) The Nubian Past of the Sudan. London and New York: Routledge.

Fenton, S. (2003) Ethnicity. Cambridge and Malden: Polity press.

Flatman, J. (2012) The Heritage Policy Group: Policy Development and Communities Engagement at the UCL Institute of Archaeology. Archaeology International. 15. 35–39. [online] Available from: http://www.ai-journal.com/articles/10.5334/ai.1501/ [Accessed 10 October 2016].

Gauntlett, D. (2002) Media, Gender and Identity. London: Routledge.

Gill, R. (1996) Discourse Analysis: practical Implementation. In Richardson, J. Handbook of Qualitative Research. BPs Books.’ [Online] available from http:/adrienneevans.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/gill_discourse_analysis1.pdf [25 December 2016].

Graham, B. and Howard, P. (2008) Heritage and Identity, The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. Burlington and Surrey. England. Ashgate publishing limited. Ashgate publishing Company.

Greer, S. (2010) Heritage and empowerment: community‐based Indigenous cultural heritage in northern Australia. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 16:1-2. 45-58. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250903441754?needAccess=true [Accessed 19 October 2016].

Hall, S and du Guy, P. (1996) Question of cultural identity. London: sage publications Ltd. California: sage publication. New Delhi: sage publications India pvt ltd. Singapore: sage publications Asia pacific Ltd.

Hall, S. (1996) introduction, who needs identity. Question of cultural identity London: sage publications Ltd. California: sage publication. New Delhi: sage publications India pvt ltd. Singapore: sage publications Asia pacific Ltd. 1-18.

Hall, S., Held, D., Hubret, D. and Thomson, K. (1996) Modernity, an introduction to modern societies. Massachusetts. Oxford: The Open University. Blackwell publisher Inc.

Hamilton, P. and Shopes, L. (2008) Oral History and Public Memories. Phiaddepiha: Temple University Press. [online]. Available from: ProQuest Library. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/bham/reader.action?docID=10255148 [Accessed 09 May 2016]

Hardy, M. (2015) The Southeast Archaeological Centre at 50 — New Directions towards Communities Engagement and Heritage Education. Journal of Communities Archaeology and Heritage, 2:3. 208-220. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1179/2051819615Z.00000000043?needAccess=true [Accessed 13 October 2016].

Hardy, T. (2013) Felling the past: embodiment, place and nostalgia. Memory and Identity in Europe Today. . London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis group.

Harrison, R. (2013) Heritage Critical Approaches London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis group.

Hobsbawm, R and Ranger, T. (1983) The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University press.

Hodges, A. and Watson, S. (2000) Community-based Heritage Management: a case study and agenda for research. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 6:3. 231-243. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250050148214?needAccess=true (Accessed 19 October 2016).

Howard, P. (2003) Heritage Management, Interpretation, Identity. London and New York: Library of Congress. Continnum.

International Rivers people, water and life (no date) Merowe Dam, Sudan. Available at: https://www.internationalrivers.org/campaigns/merowe-dam-sudan-0 (Accessed: 18 October 2016)

Jan, D and Pedroli, B. (2011) Perspectives on Landscape Identity: A Conceptual Challenge. Landscape Research. 36:3. 321-339. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/01426397.2011.564860 [Accessed 10 June 2016].

Jones, R. (2012) Discourse Analysis. London and New York: Routledge.

Jorgensen, B and Stedman, R. (2001) Sense of Place as an attitude: Lakeshore Owners attitudes towards their property. Journal of Environmental Psychology. Academic Press. 21, 233-248. [online] Available from: http://www.wsl.ch/info/mitarbeitende/hunziker/teaching/download_mat/07-2_Jorgenson_Stedman_2001.pdf [Accessed 20 December 2016].

Jorgensen, M and Phillips, L. (2002) Discourse analysis theory and method’. London and California: Sage.

Jorhensen, M. and Phillips,M. (2002) Discourse analysis as theory and methods. London. Thousand Oaks. New Delhi: Sage.

Kaltmeier, O. (2016) Heritage, Culture and Identity: Selling Ethnicity: Urban Cultural Politics in the Americas. [online]. Farnham: Ashgate. Available from: ProQuest Library. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/bham/reader.action?docID=10456144 [Accessed 10 May 2016].

Kane, S. (2003) The Politics of Archaeology and Identity in a Global Context. The Archaeological Institute of America.

Kato, K. (2006) Community, Connection and Conservation: Intangible Cultural Values in Natural Heritage—the Case of Shirakami‐sanchi World Heritage Area. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 12:5. 458-473. [Online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250600821670?needAccess=true [Accessed 19 March 2017].

Keitumetse, S and Pampiri, M. (2016) Communities Cultural Identity in Nature-Tourism Gateway Areas: Maun Village, Okavango Delta World Heritage Site, Botswana. Journal of Communities Archaeology and Heritage. 3:2. 99-117. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxye.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/20518196.2016.1154738 [Accessed 10 January 2017].

Kendall, T (2010) Jebel Barkal History and Archaeology of Ancient Napata. Available at: http://www.jebElbarkal.org/ (Accessed: 18 July 2016).

Lecompte, M and Schesul, J (2010) Designing and Conducting Ethnographic Research. Plymouth: AltaMira press.

Lenik, S. (2013) Communities engagement and heritage tourism at Geneva Estate, Dominica. Journal of Heritage Tourism. 8:1. 9-19. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/1743873X.2013.765737?needAccess=true [Accessed 15 October 2016].

Litter, J. (2008) Heritage and Race, The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. Ashgate publishing limited. Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate publishing Company.

Little, B.J. and Shackel, P.A. (2014) Archaeology, Heritage, and Civic Engagement. California: Left Coast Press.

Macdonald, S. (2013) Memory and Identity in Europe Today. London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis group.

Marschall, S. (2008) The Heritage of Post-Colonial Societies. The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity Ashgate publishing limited. Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate publishing Company.

McDowell, S. (2008) Heritage, Memory and Identity, The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. Ashgate publishing limited. Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate publishing Company.

McLean, F. (2006) Introduction: Heritage and Identity. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 12:1, 3-7. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250500384431 [Accessed 18 June 2016].

Merriam, S. (2002) Introduction to Qualitative Research. San Francisco, U.S.A: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Merriam, S. (2009) Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco, U.S.A: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Moore, N. and Whelan, Y. (2012) Heritage, Memory and the Politics of Identity. [online]. Ashgate. Available from My Library http://lib.myilibrary.com.ezproxye.bham.ac.uk/Open.aspx?id=110357 [Accessed 10 May 2016]

Munjeri, D. (2004) Tangible and Intangible Heritage: from difference to convergence. Museum International. 65. 1-2. Blackwell Publishing. Oxford: [Online] Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1350-0775.2004.00453.x/epdf [Accessed 19 March 2017].

Mydland, L. and Grahn, W. (2012) Identifying heritage values in local communities. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 18:6. 564-587. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527258.2011.619554?needAccess=true [Accessed 22 October 2016].

O’Neill, M. (2006) Museums and Identity in Glasgow. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 12:1, 29-48. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250500384498 [Accessed 19 June 2016].

Patton, M. (1990) Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Beverly Hills. CA: Sage. 169-186.

Perkin, C. (2010) Beyond the rhetoric: negotiating the politics and realising the potential of community‐driven heritage engagement. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 16:1-2. 107-122. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250903441812?needAccess=true [Accessed 15 October 2016].

Petrov, K (1989) ‘Memory and oral tradition’, in Butler, T Memory history, culture and mind. Network: First Blackwell ltd. pp 77-94

Punch, K. (2005) Introduction to Social Research Quantitative and Qualitative Approach. 2nd edn. London: Sage

Rampley, M. (2012) Heritage, Ideology and Identity in Central and Eastern Europe, Contested pasts, Contested presents. The International Centre for Cultural & Heritage Studies. Woodbridge. UK. Newcastle University. The Boydell Press.

Rose, G. (2001) Visual Methodologies: an introduction to researching with visual materials’. Los Angeles. London. New Delhi. Singapore: Sage.’

Rose, G. (2007) Visual Methodologies. London: Sage.

Rose, G. (2012) Visual Methodologies: an introduction to researching with visual materials.3ed. Los Angeles. London. New Delhi. Singapore: Sage.

Rose, G. (2013) On the Relation Between ‘Visual Research Method’ and Contemporary Visual Culture. The Sociological Review, 61, 709-727.’ [Online] available from

Rotman, D. and Preece, J (2010) The ‘WeTube’ in YouTube – creating an online communitiesthrough video sharing. International Journal Web Based Communities, 6(3), 317-333.

Schofield, J and Szymanski, R. (2011) Local Heritage Global Context, Cultural Perspectives on Sense of place. . Ashgate publishing limited. Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate publishing Company.

Silverman, D. (1993) Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction. London: Sage Publications.

Skeates, R. (2004) Debating the Archaeological Heritage. Duchwoth Debates in Archaeology. Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd. London.

Smith, A. (2003) Landscape Representation: Place and Identity in Nineteenth-Century Ordnance Survey Maps of Ireland. Landscape, Memory and History, Anthropological Perspectives. Anthropology Culture and Society. Pluto press.

Smith, L. (2006) Uses of Heritage. London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis group.

Smith, L. (2008) Heritage, Heritage, Gender and Identity, The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. Ashgate publishing limited. Surrey. England. Ashgate publishing Company. Burlington. USA.

Smith, L (2015) Intangible Heritage: A challenge to the authorised heritage discourse. 4. 133-142. Revista d’etnologia de Catalunya. [online] Available from: http://www.raco.cat/index.php/RevistaEtnologia/article/view/293392/381920 [Accessed 10 October 2016].

Smith, L. (2006) Cultural Heritage, Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural studies. London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis group.

Smith, L. and Akagawa, N. (2009) Intangible Heritage. London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis group

Smith, L. and Waterton, E. (2009) Heritage, Communities and archaeology. Duchwoth Debates in Archaeology. . London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd.

Stephens, J. (2014) ‘Fifty-two doors’: identifying cultural significance through narrative and nostalgia in Lakhnu village. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 20:4. 415-431. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527258.2012.758651?needAccess=true [Accessed 19 December 2016].

Stevens, M., Flinn, A. and Shepherd, E. (2010)New frameworks for communities engagement in the archive sector: from handing over to handing on. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 16:1-2, 59-76. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250903441770?needAccess=true [Accessed 19 October 2016].

Stewart, P and Strathern, A. (2003) Landscape, Memory and History, Anthropological Perspectives. Anthropology Culture and Society. Pluto press.

Stig Sorensen, M.L. and Carman, J. (2009) Heritage Studies Method and Approaches. . London. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis group.

Stobbelaar, D. and Bas Pedroli, B. (2011) Perspectives on Landscape Identity: A Conceptual Challenge. Landscape Research. 36:3. 321-339. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/01426397.2011.564860?needAccess=true [Accessed 19 October 2016].

Taylor, K and Lennon, J. (2012) Managing cultural landscapes. USA. Canada: Routledge.

Teather, E. and Chow, C. (2010) Identity and Place: the testament of designated heritage in Hong Kong. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 9:2, 93-115. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxye.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250304772 [Accessed 19 December 2016].

Thomas, S. and Lea, J. (2014) Public Participation in Archaeology. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press.

Tim Murray, T (2011) Archaeologists and Indigenous People: A Maturing Relationship. Annual Reviews. Anthropol. 40.363–78. [online] Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-anthro-081309-145729 [Accessed 18 October 2016].

UNESCO (2003) Gebel Barkal and sites o the naptan region. Available at: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1073/ (Accessed: 18 December 2016)

UNESCO (2003) The convention for the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage. Available at: http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/en/convention (Accessed: 09 November 2016)

Vienni, B. (2014) Interdisciplinary socialization of archaeological heritage in Uruguay. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development.4:1. 95 – 106. Emerald Insight. [online] Available from: http://www.emeraldinsight.com.ezproxye.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdfplus/10.1108/JCHMSD-11-2012-0066 [Accessed 10 December 2016].

Vong, L. (2015) The mediating role of place identity in the relationship between residents’ perceptions of heritage tourism and place attachment: The Macau youth experience.Journal of Heritage Tourism. 10:4,344-356. Routledge Taylor & Francis group. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/1743873X.2015.1026908 [Accessed 10 October 2016].

Waterton, E. (2005) Whose Sense of Place? Reconciling Archaeological Perspectives with Communities Values: Cultural Landscapes in England. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 11:4. 309-325. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250500235591?needAccess=true [Accessed 19 October 2016].

Waterton, E. and Smith, L. (2010) The recognition and misrecognition of communities heritage. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 16:1-2. 4-15. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250903441671?needAccess=true [Accessed 19 October 2016].

Waterton, E. and Watson, S. (2016) Heritage and Communities Development: Collaboration or Contestation. Academia. [online] Available from: https://www.academia.edu/433748/Heritage_and_Community_Engagement_Finding_a_New_Agenda [Accessed 19 October 2016].

Waterton, E., Smith, L. and Campbell, G. (2006) The Utility of Discourse Analysis to Heritage Studies: The Burra Charter and Social Inclusion. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 12:4, 339-355. [online] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/13527250600727000?needAccess=true [Accessed 19 October 2016].

Werber, M. (1968) Economy and society. Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Witich. Berkeley: University of California press.

Werbner, R. and Ranger, T. (1996) Postcolonial Identities in Africa. Zed Books Ltd.

Wertsch, J. (2002) Voices of Collective Remembering. Cambridge University press. World Heritage site (no date) Gebel Barkal. [online] Available from:

http://www.worldheritagesite.org/sites/site.php?id=1073 [Accessed 19 October 2016].

Appendix

In-depth interviews schedule

Local community samples

Main question 1:

What can you tell me about this archaeological site?

Sub-questions:

How long have you been living close to the site?

What do you know about this site?

What do you like/dislike about it?

Do you go there, why, how often, with whom, what do you do there?

Do you speak to each other (friends, family, neighbours) about the Site? What do you say?

Main question 2:

How do you feel about the work conducted in the site?

Sub-questions

Who works in the Site? What do they do? What do you think of that?

How do they deal with the you as a local community?

Do you think this work can contribute something to the local community? If

yes, then how? If no, then why?

How do you see the site in the future?

Main question 3:

To whom do you think this site belong to?

Sub-questions:

When you visit the site, do you go with others sharing you same interest?

What is your action when someone break/move/take any of the archaeological remains?

What do you think/feel when the site is full of tourist?

Do you think this is a Nubian site and therefore belong to Nubian tripe and why?

Who do you think should maintain and look after the site and why?

In-depth oral historian and local community leader’s interviews schedule

Oral Historian

Main question 1:

What can you tell me about this archaeological site?

Sub-questions:

What is the historical background of this archaeological site?

How do you tell other local community members with this history?

To what extent they take this history as the right past event?

How do you tell them this history?

From where did you know this history?

How do you teach this history for the following generation?

Main question 2:

To whom do you think this site belong to?

Sub-questions:

What is your action when someone break/move/take any of the archaeological remains?

Do you think this is a Nubian site and therefore belong to Nubian tripe and why?

local community leader’s

Main question 1:

What can you tell me about this Archaeological site?

Sub-questions:

How do you often visit this site?

Why do you visit this site?

What do you tell other local community member about this site and what do they tell you?

Main question 2:

What are the local community’s active social groups that have a direct involvement with this site?

Sub-questions:

What is their role?

What is their activities?

Are they competing or collaborating with each other?

How does each of these groups seen/view the site and its past?

Is any of this groups belong to one tribe?

Is any of this groups excluded the membership to one gender than other?

Main question 3:

To whom do you think this site belong to?

Sub-questions:

What is your action when someone break/move/take any of the archaeological remains?

Do you think this is a Nubian site and therefore belong to Nubian tripe and why?

Figure 10: The interview questions sample

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Archaeology"

Archaeology is the field of study that focuses on the discovery, recovery and studying of objects and remains. Archaeologists analyse the objects and remains that are discovered, using them to develop a greater understanding of past generations and species.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: